Signposts

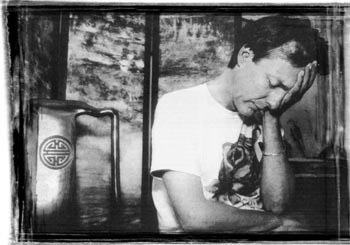

Aftermath: Marc Klaas paused the day after police found the remains of his missing 12-year-old daughter, Polly. The highly publicized murder led Klaas to push for stringent sentencing laws.

5 underreported stories that marked our times

By Greg Cahill

OVER THE PAST five years, Sonoma County has seen phenomenal growth. Traffic congestion and frustration, friction between the rural and urban elements, the burgeoning grape-growing industry and its impact on the environment, the skyrocketing cost of housing, the threat of street gangs, and the travails of local government and public officials–all of these events challenge us, spurring a search for answers.

As the community comes to grips with those changes, the Independent has sought to provide a broader voice in the community–though the newspaper has not always danced to everyone’s tune. Our news and features have resulted in a boycott by progressives, a lunchtime picket by angry gender crusaders, and more than a few threatening phone calls from irate gun owners, all reinforcing that old journalistic adage that if you’re not pissing someone off, you’re not doing your job.

There was no shortage of stories over the past five years that mirror this patch of flawed paradise we call home. The threat of the ever-encroaching mall culture. The inadequacy of local law enforcement’s response to domestic violence, rape, and sexual assault cases. The globalization of the local wine industry. The environmental degradation of the Russian River. The endless quest to flush Santa Rosa’s wastewater. The challenge of learning to live with HIV. The creation of a sane legacy for our children0.

Here are five stories published between 1994 and 1999–and revisited for updates–that serve as signposts for that nebulous thing called quality of life–the way we live, who we are, what we make of this world.

The Selling of Marc Klaas

“It’s almost too difficult to talk about all of this,” says Marc Klaas, picking through a plate of Belgian waffles and blueberries at a noisy Petaluma café across the street from the storefront that served as the first Polly Klaas Volunteer Search Center.

“We miss her more than ever,” he adds, his voice cracking with emotion and barely audible above the din of clattering dishes and Baroque music booming from the sound system. “It doesn’t get any easier–not at all. She’s just this little memory that’s always going to be 12 years old now.

“God almighty–it’s so fucked up.” . . .

That was the scene a couple of weeks shy of the first anniversary of the ill-fated night when a knife-wielding bearded stranger–later identified as ex-con Richard Allen Davis–carried Klaas’ daughter barefoot and sobbing from the bedroom of her quiet westside Petaluma home into the moonlit night on Oct. 1, 1993.

For nine sorrowful weeks, the world had focused its attention on Petaluma, where an army of volunteers and police searched in vain for the girl who became known as America’s Child. In a media frenzy, hordes of reporters and film crews from around the globe converged on this usually quiet community.

By the time police discovered Polly’s body on Dec. 4 beneath a pile of debris at an old sawmill just south of Cloverdale, Marc Klaas was a media star–an angry man crying for justice. His ordeal earned him a front-row seat in a legal battle for tougher sentencing laws that social justice advocates–and later even Klaas himself–would regard as a draconian nightmare.

In an exclusive 1994 interview, Klaas discussed with the Independent all the ways that he and others manipulated the media to keep Polly in the public eye, only to be manipulated in return by image-savvy news hounds and struggling politicians–including President Clinton and Gov. Pete Wilson–all looking for Three Strikes to boost their careers.

With the Three Strikes law already adopted by the state Legislature, Klaas argued in vain during the interview against a then-impending state ballot initiative that would make it even tougher to rescind statutes that sent any three-time felon to jail for 25 years to life, even for non-violent offenses. “I just don’t happen to think that stealing a basketball, which is considered a serious non-violent crime . . . should be held over somebody’s head for the rest of their life,” he said at the time.

The first legal challenge for the new state law came months later–a Sonoma County case in which Superior Court Judge Lawrence J. Antolini had refused to throw the book at a transient convicted of stealing cigarettes. The higher courts overruled Antolini, declaring that judges had almost no discretion in these matters.

Since then, 80 percent of the 50,000 felons sentenced under Three Strikes (now in effect in 23 states) were convicted for non-violent crimes, fueling a prison-construction boom that critics say has undermined funding for public education and threatens to stall the state’s high-tech economic engine.

As for Klaas, he is living in Sausalito and still involved in child-safety issues, but for the most part he has dropped out of the limelight.

Mean Streets

Bam-bam. Bam-bam-bam-bam. Two bursts. Six shots. The piercing snap of gunfire in the night is routine for Santa Rosa resident Kathy Ferrell, and so is fear. “Of course I’m scared,” she says. “What goes through your head is: ‘I just hope a bullet doesn’t come up here and hit my daughter.’ I pray every night that it doesn’t hit one of my children.

“Why doesn’t somebody do something about it?” she asks. “I mean, the police are down here all the time, but always after the fact. I guess that’s the way it is with crime. I, myself, as a person, am fed up.” . . .

Back-street boys: Apple Valley Lane/Papago Court area teens posed in 1996 for an article about an area deemed “the most dangerous neighborhood” in Sonoma County. Gangs are still a problem, but things have improved, police say.

That was March 1996. After reading a three-inch item tucked in the back of the local daily describing a gang-related shooting and noting that local police had dubbed the Apple Valley Lane/Papago Court neighborhood that Ferrell and a few hundred other Santa Rosans called home “the most crime-ridden neighborhood in Sonoma County,” an Independent contributor set out for an in-depth examination of the situation. What he discovered was high crime and social decay exacerbated by absentee landlords, official neglect (the Santa Rosa City Council had promised low-interest loans to homeowners but failed to follow through on the pledge), a community wracked by ethnic differences, and police frustrated by limited resources.

Three years later, it’s still a rough neighborhood, but things have changed for the better. “There are still significant issues, but there is some neat stuff, too,” says Santa Rosa Police Chief Michael Dunbaugh. In 1998, the SRPD received a community crime-resistance grant that funds two patrol officers in the area. The 7-Eleven Corp. donated space for a police substation; local Asian, Hispanic, and Eritrean residents formed a multicultural center to help foster greater understanding and ease tensions; and a new neighborhood youth center is set to open soon.

“There are still problems associated with absentee landlords and gang issues, but there also is a lot of great dialogue underway in that neighborhood,” says Dunbaugh. “The neighborhood definitely is beginning to demonstrate a greater ability to push the gangs out.”

Sour Note

It just didn’t feel right. From the start, Raoul Goff, his three brothers, and their colleagues–with their “BMWs, cell phones, and cartel ponytails,” as one local describes them–stood out starkly amid the slow pace and quaint Victorian storefronts along the quiet streets of Occidental, the small west county town best known for its Italian restaurants and as a refuge for old-time hippies.

But it wasn’t just the newcomers’ stylish dress or their sometimes arrogant manner that seemed out of place to folks hanging around the popular Union Hotel saloon. There also were persistent rumors that Goff, a 35-year-old Sonoma County native, and some of his cohorts–who last year bought into a non-profit public trust that includes a kids’ camp, ecology center, redwood groves, oak woodlands, and grassy ridge tops–are devotees of the Hare Krishna faith, a secretive sect with a checkered past.

Some grumbled that Ocean Song’s new partners had concealed that fact. . . .

In July 1996, the Independent broke the story that Goff, the head of a San Francisco-based environmental organization called EcoCorps, had ambitious plans to transform the Ocean Song Farm and Wilderness Center into a busy religious retreat–a direct violation of the purchase agreement. Staff members at the beloved coastal retreat complained that EcoCorps had played a major role in the financial collapse of the organization and that the San Francisco partners had plans to take over the project altogether.

The story disclosed Goff’s connections to the Hare Krishna sect through past associations with a renegade Krishna leader who in the 1980s had created an armed camp outside of Hopland and with which Goff’s far-flung publishing interests had close ties.

As a result of the investigation, community members redoubled their effort to find partners to purchase Ocean Song and return the center to its original mission. These days, the supporters of Ocean Song are singing a happier tune. Former Green Bay Packer-turned-businessman Andrew Beath, 54, paid $800,000 of the $1.3 million paid to the Goffs for the coastal hillside property. But the fix is only temporary. Former staff members, who have raised $500,000 toward an option to purchase the land from Beath, have just 18 months to complete the deal. If they fail, Beath can resell the property.

Timber Wars

Upstream from everywhere in the Sonoma County basin, the evergreen mountains of Alpine Valley are home to spotted owls, towering Douglas firs, spawning salmon, and privacy-loving humans. St. Helena Road winds like a serpent through the valley. . . . In recent months, this idyllic forest setting has become a volatile battleground. . . .

Under a growing number of complaints from local residents frustrated by bureaucratic roadblocks in the efforts to deal with the plethora of logging underway in the county–much of it by vineyards coveting lucrative hillside plots prone to erosion and environmental degradation–the Independent in November 1997 presented the anatomy of a timber harvest plan, laying out in detail how the local logging industry had pushed hard on an Alpine Valley neighborhood northeast of Santa Rosa. At the time, E&J Gallo, Kendall-Jackson, and other North Coast vineyards were slicing through the county’s forests with little or no resistance from state and federal regulators, who virtually turned their backs on catastrophic timber harvests as long as the cuts were made to further agriculture.

The problem of “urban interface,” when quiet country living and the roar of chain saws collide, is still common, despite the adoption of a new hillside-planting ordinance advocated in the article and worked out over this past summer by growers and conservationists. Indeed, with implementation of the new county regulations just weeks away, vineyard developers–including those at pristine Quail Hill in rural Freestone–have redoubled their efforts to beat the October deadline and are bulldozing hilltops into local creeks at an alarming rate.

Meanwhile, former county Supervisor Ernie Carpenter stunned supporters earlier this year when he announced that he is working as a consultant for a proposed 4,000-acre vineyard conversion project–part of a massive 10,000-acre project that extends through west county into Mendocino County–that would lop down forests for the largest coastal winery in Northern California.

Jailhouse Blues

Joan McMillan’s journey “through hell and back” started last April [1998] on a short bus ride from the honor farm near the Santa Rosa Airport to the Sonoma County Jail’s main adult detention facility. Six months pregnant and busted for supplementing her welfare income, the 44-year-old faced jeers from male inmates sharing the ride. “I started having contractions,” she recalls. “I already had some [pregnancy] complications.”

It was a bad omen. At the jail, correctional officers placed McMillan in a tiny holding cell for nine hours, she says, and her physical condition began to deteriorate. “After eight hours I was experiencing dizziness and almost blacking out,” McMillan recalls. “My body was going into some kind of weird shock. I was sweating and I lay on the floor, freezing and shaking. . . .

“The next thing I knew, a female guard was kicking me on my hips and thighs, calling me ‘drama queen’ and ‘bitch.'”

That night the county jail staff moved her to an infirmary cell, but things didn’t improve, McMillan says. “I was throwing up, dehydrated, a total wreck,” she remembers.

“The medical treatment was horrible. I would ring the emergency buzzer when I was having contractions, but the guards, especially the younger ones, seemed preoccupied at the computers. They would ignore the buzzers as long as they could.”

The harrowing tales of neglect and alleged abuse at the Sonoma County Jail published in July of 1998 questioned the treatment of inmates and revealed that the health-care provider at the facility had an ugly past.

The two-part series earned the Independent the 1999 Lincoln Steffens Award for investigative reporting, and culminated three years of articles chronicling in-custody deaths, rampant sexual harassment of female sheriff’s deputies and correctional officers, and a porn scandal involving on-duty guards.

But change comes slowly at the beleaguered institution.

Assistant Sheriff Sean McDermott recently announced his plans to step down as jail chief as soon as a replacement is found. And the county Board of Supervisors has pledged to place the health-care provider’s contract renewal on the agenda next year for public debate.

New allegations continue to pour in to the newspaper from inmates.

Yet the public has shown little interest in the way inmates are treated or whether tax dollars are spent on possibly inadequate medical services.

As Abolition Road activist Charla Greene told the Independent last year, “Public opinion is against inmates.

“The feeling is they did something bad, so let them be treated bad.’ ”

From the August 19-26, 1999 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.

© Metro Publishing Inc.