Gently Kicking Ass

The gentlemanly sport gets a new recruit

By M. V. Wood

In Japanese, the word “judo” means “gentle way.” Brute force is shunned. Instead, it’s a sport where strength merges with grace, a gentleman’s game emphasizing character and honor. So it didn’t help the reputation of Graton’s Lance Lameyse one tiny bit when he broke all official rules and social mores by attempting to pummel his opponent’s face during the 2000 Senior Nationals.

The outburst seemed to cement Lameyse’s standing as a ruffian who would never amount to much. It comes as some surprise, then, that he’s not only returning to compete in the 2002 Senior Nationals, April 12 and 13 in Cleveland, but he’s playing with the blessings of the sport’s upper echelons. As the newest judo recruit at the Olympic Training Center, the former black sheep is stepping onto the mat as an insider.

“I thought the 2000 Nationals was going to be the end of my judo career. But it turned out to be my lucky break,” Lameyse says.

The 26-year-old athlete started taking lessons at age five, in his hometown of Graton. Back in those days, Graton was still considered a seedy area full of outlaws and hillbillies, and surrounding communities referred to the young, local males as “the Graton Boys.” It wasn’t the type of place you’d expect to find judo classes. But one day an assistant chief at the local volunteer firehouse parked the fire engines outside, placed a bunch of mats on the station floor, and announced that class was in session.

“What can I say–we were a bunch of outback hillbillies doing judo,” Lameyse recalls. “But we had a blast.”

After three years at the firehouse, Lameyse started training in Berkeley with judo champion David Matsumoto. He became a skilled athlete in his 10 years there, but eventually quit taking lessons. “I was young, and I thought I could do it all on my own,” he says. “I figured I was good, and I just had to show up at the tournaments and do my best.”

Although Lameyse was talented enough to place nationally, he didn’t have enough knowledge of the game’s strategy to win gold or silver. And slowly his dreams of playing in the Olympics started to fade.

“I wasn’t going far with the judo,” he said. “I’d get third place here and there, but I couldn’t break into the top level. Plus, I was a total outsider. I didn’t even have a coach; I was totally out of the loop. I had always dreamed of going to the Olympics, but I couldn’t even get an invitation to train at the [Olympic Training Center]. And while I was putting all my energy into this dream that I couldn’t grab hold of, I was letting all the other parts of my life slide. I wasn’t working on a career. I wasn’t starting a family. Nothing.”

Those childhood taunts of how Graton Boys never amount to anything were ringing in his ears long before he stepped onto that mat during the 2000 Nationals.

As usual, the match started off with the two opponents trying to get a good grip on each other’s collars. A firm, well-placed grip is all-important to a favorable outcome, and the top players are very aggressive about getting just the right hold. It’s against the rules to punch. But if in the process of trying to get a good grip, your opponent’s face happens to get in the way of your fist, well, that’s just part of the game.

Still, it’s a gray area of the sport. The referee has to not only judge a player’s actions, but he must also try and interpret the player’s intent. And for someone from the wrong side of the tracks–a Graton Boy accustomed to having his actions misinterpreted–it’s a great luxury to have the confidence to step into such a gray area. So Lameyse avoided it.

But then there was his opponent, a student at the Olympic Center. And at his side of the mat, yelling out instructions and encouragement, was Edward Liddie, one of the country’s most respected judo coaches. To Lameyse, it seemed his opponent didn’t hesitate a split second in trying to get a good grip, even though that meant hitting Lameyse in the face repeatedly. There was no hint of fear in his eyes that maybe, just maybe, the referee might think he was cheating and trying to sneak in a punch.

Perhaps it was this very aplomb with which his opponent stepped into the gray zone that taunted Lameyse the most. In his eyes, this adversary was a privileged son who had the confidence to fight full-force in the knowledge that his actions would always be viewed with the benefit of a doubt. At that moment, Lameyse felt he would never have that privilege, nor that fighting edge. And it was probably at this very moment that Lameyse attempted to punch his opponent in the face.

None of the punches even connected. So, although Lameyse was disqualified from the match, he was allowed to continue competing in the tournament.

Though he placed third, Lameyse says, “I wasn’t very proud of my performance that night. The only reason I got the bronze was because I happened to catch the other guy off guard. I trudged through that entire tournament. I showed no finesse, I didn’t feel in control. I just sweated it out. After that competition, I felt beaten.” Lameyse was ready to give up on his dreams. That’s when he received a call from Sandro Mascarenhas.

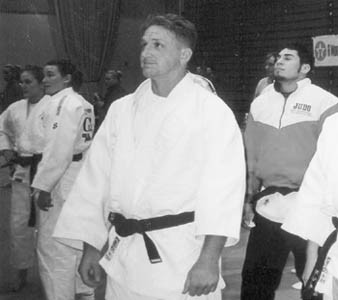

A judo player in San Francisco, Mascarenhas always considered Lameyse to be a good guy at heart–just a little misunderstood. And when he heard the stinging rumors following the 2000 Nationals, he wanted to help. So he talked things over with nationally renowned coach Mitchell Palacio, who heads the largest judo club in the country and was ranked one of the country’s top three judo athletes for 20 consecutive years. The two offered to take Lameyse under their wing and give him individualized training and guidance.

“[Lameyse] was making a lot of mistakes because he didn’t have any guidance for this elite level,” explains Palacio. “At this stage, everyone has the basic skills, so what it comes down to is strategy and a game plan. And that’s what he lacked. But Lance has raw talent. And that raw talent alone would put him in the top three, without any strategy.”

Lameyse’s game improved so dramatically that he soon won silver at an international tournament and was recruited by the Olympic Center. He’s been there since January.

Lameyse says that Palacio and Mascarenhas taught him more than new skills and strategy. “They showed me how my attitude was getting in the way of my game, and my life. Let’s just say they made it clear that people didn’t have a problem with where I was from. They had a problem with how I was acting.

“Before all this happened, I didn’t really believe in altruism. But Sandro and Mitchell went out of their way to help me. Ever since I was little, I heard that judo is more than a sport; it’s a way of life . . . it’s a gentleman’s game. I guess those guys like to teach by example.”

From the April 4-10, 2002 issue of the North Bay Bohemian.