George Takei keeps cracking himself up.

Over the course of an hour-long phone interview with the 76-year-old actor, social-media icon and former helmsman of the starship Enterprise, Takei bursts into his boisterous, unmistakable laugh nearly a dozen times.

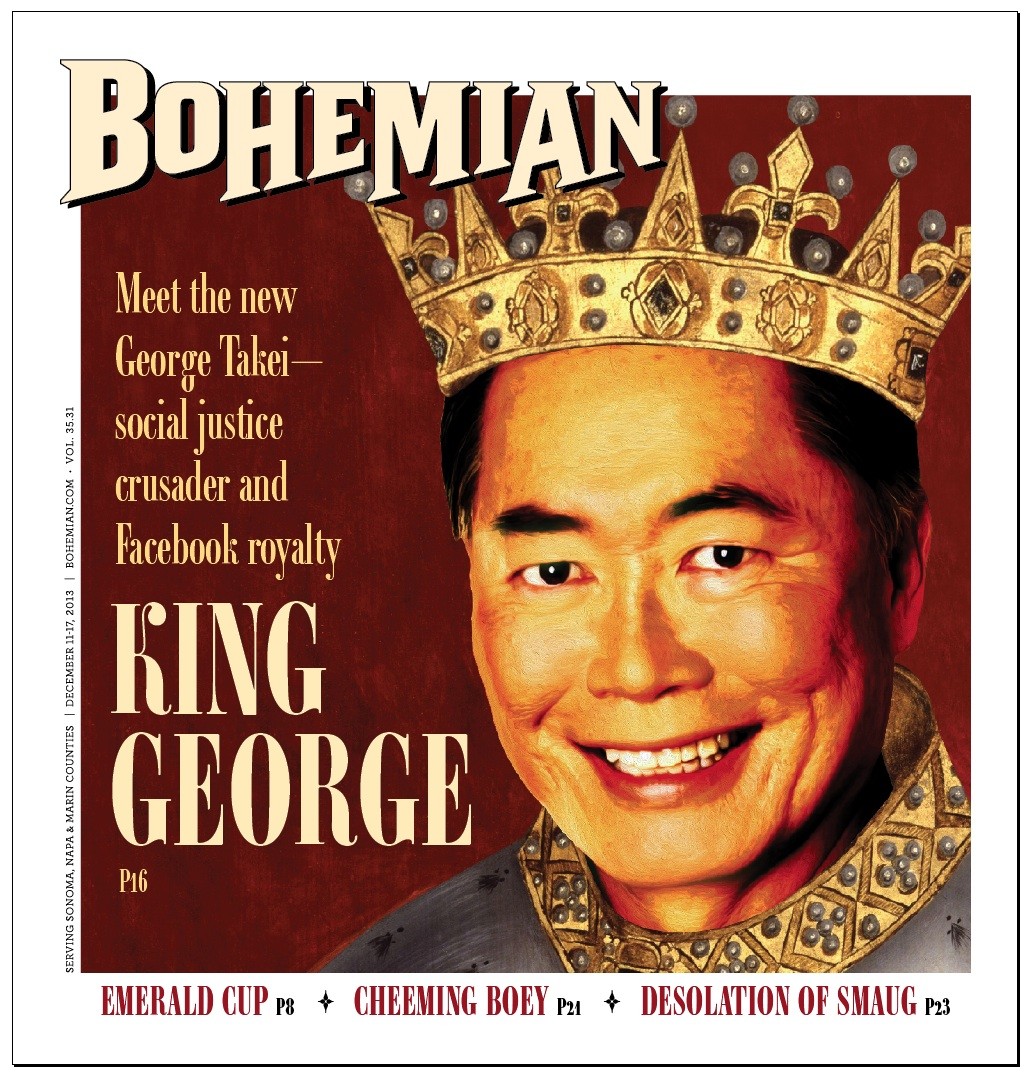

And quite frankly, why shouldn’t he be happy? He’s had a show business career that’s spanned more than 50 years, and now Takei has become a royal fixture on social media—with a Facebook page of nearly 5.2 million likes and a Twitter account of more than 916,000 followers.

And while Takei lives to entertain, he’s spent even more of his time and effort fighting for social-justice issues. In his early life, he marched with Dr. Martin Luther King and protested the Vietnam War. In 2005, he came out publicly as a gay man after spending decades of hiding to preserve his career. Since, he’s led a tireless crusade for marriage equality, marrying the love of his life and partner of more than 25 years, Brad Altman, in 2008.

It’s a life he cherishes, but doesn’t take for granted.

‘You have to approach every day like it’s going to be a wonderful day,” Takei says. “And sure it may rain or get cold, but you have to find something every day to be thankful for, and turn that into your salad days. Every day should be a salad day, as long as we’re mindful of the fact that there’s always room for improvement.”

It’s no surprise that he approaches life with such an optimistic outlook. George Takei had to start searching for life’s silver linings at a very young age.

In 1942, at the age of five, he and his family were living in Los Angeles when they were removed from their home by American soldiers. It was just a few months after the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor; President Franklin Roosevelt had signed an executive order that permitted the removal of any citizen of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast.

It’s a day, Takei says, that he’ll never forget.

“My brother and I were in the living room looking out the front window and I saw two soldiers with bayonets on their rifles—I remember the sparkle on the bayonets from the sun—coming up the driveway and stomping onto our porch, and we were ordered out of our home,” Takei says. “My father and brother and I went outside, and my mother was the last to come out. She came out with my baby sister in one hand and a large duffel bag in the other, and tears were streaming down her cheek.

“A child never forgets that image. It was terrifying.”

At the time, the construction of the camps was not yet complete, and the Takei family, along with many other Asian Americans, was taken to Santa Anita Racetrack to be housed “in this narrow, smelly horse stall.” But even then, young Takei looked for the bright side. “As a five-year-old boy, I remember thinking, I get to sleep where the horsies sleep. I thought it was fun,” he recalls.

The Takeis remained at Santa Anita for several months before being loaded onto a train and shipped to the Rohwer War Relocation Center in “the swamps of Southeast Arkansas,” as Takei remembers. As a child, he says, he was able to view the camp with a sense of normalcy. Barbed-wire fences, searchlights following his nightly trips to the bathroom and armed soldiers in sentry towers all seemed ordinary.

[page]

“It all just became part of the landscape,” Takei says now. “A child is amazingly adaptable, and what can be seen as grotesquely abnormal in normal times became my normality.

“Although I remember, with quite a bit of irony, starting school in that camp every morning by reciting the Pledge of Allegiance. I could see that barbed wire fence every morning as I recited those words: ‘With liberty and justice for all.'”

It wasn’t until Takei was a few years removed from the camps that he started to question his childhood incarceration. He began talking to his father, Takekuma “Norman” Takei, about what had happened and what, if anything, he was supposed to do about it. His father told him that the government was only as great and as fallible as its people were. It was a citizen’s responsibility, he advised, to be engaged in the democratic process.

And so from a very young age George Takei spoke about his imprisonment in an effort to educate the American people. He also became engaged in electoral politics. Shortly after one of his talks with his father, the elder Takei took young George to the Los Angeles headquarters of Adlai Stevenson presidential campaign—”My father was a great admirer of Adlai Stevenson,” says Takei—and signed him up as a volunteer.

“Although I supported Stevenson, and he lost,” says Takei. “Then I worked for Jerry Waldie for governor of California, and he lost. Then I supported George Brown for the U.S. Senate, and he lost. So when I was asked by our city councilman Tom Bradley to head up his Asian-American committee, I said to him, ‘Are you sure? I have been the curse of loss for so many candidates.’ But finally with Tom Bradley, we won, and he became the first African-American mayor for the city of Los Angeles—and the only mayor to serve five terms.”

Yet even as Takei tirelessly championed social justice issues while his acting career progressed, he avoided public battles for the very cause that was probably the closest to his heart: LGBT rights and equality.

As a young actor working in Hollywood, Takei decided to keep his life as a gay man secret. Today, he matter-of-factly says his decision was “the reality of the times.”

“I was deeply involved in the Civil Rights movement,” Takei says. “But when it came to LGBT issues, I was silent throughout the ’60s, ’70s, ’80s and ’90s, because I was pursuing a career as an actor.

“In television, you want ratings, in movies, you want box office. And unfortunately at that time, the feeling was you wouldn’t get any of that if you were known as a gay actor. Early in my career, I was a young, no-name actor going up for part after part and getting rejected time and time again because you’re too tall, too short, too skinny, too fat, too Asian or not Asian enough. To be out as an actor—well, you weren’t really an actor at all because you couldn’t work.”

Hiding something so important to his happiness was tough for Takei, who recalls an ever-present fear of being exposed as living a double life. He would be seen in public with female friends at parties and openings one night, while frequenting gay bars the next.

Oddly enough, it was another actor who helped him make the decision in 2005 to come out from under that cloak. Both houses of the California Legislature had approved marriage equality legislation, and all it took for ratification was the signature of then-governor Arnold Schwarzenegger. Takei says despite the fact that Schwarzenegger was a Republican, he still expected him to sign the bill.

[page]

“When he ran, he said he was from Hollywood and he worked with actors who were gays and lesbians—he ‘had friends who were gays and lesbians’—you know, the whole cliché bit,” Takei explains. “And honestly, as a friend, I thought he would sign it. But he was a Republican and his base was the right wing. He vetoed the bill, and we were shattered—disappointed is too mild a word.”

When Schwarzenegger refused to sign the bill, people immediately began to protest in the streets against him. Takei and his partner (now husband), Brad, watched the protests unfold on television. “We were raging, too,” he says. “But we were comfortable at home.”

Takei and his partner talked it over and decided the time had come for Takei to not only speak out, but speak out “as a gay man.”

“We came so close, just one signature and this governor vetoed it. If I was going to speak out, then my voice had to be authentic,” he recalls. So while he had been out to close friends and family for years, Takei was finally out publicly—and has been a proud, steady voice for marriage equality ever since.

Takei doesn’t dwell on whether or not he should have come out sooner. While he loves his life now, he also loved his life then. But keeping quiet and living a secret life does come with regrets.

“I love children and I never had children,” Takei says. “My surrogate children have been my nieces and nephews. My nephew who lives closest to us has children of his own, and it’s provided us with surrogate grandchildren, and we love them deeply.

“But at the airport or traveling, I see the little kiddies and I do wish we could have had those experiences as parents. For example, I never got to get up with them in the middle of the night, and soon my nephew will have the experience of his daughter, who is 14, dating. I do see those experiences romantically, and I’ve lived vicariously through my nephew, and I do envy him those precious times.”

Despite any regrets, it’s obvious to see that George Takei is someone who loves his life as an activist and as an entertainer. He has managed to reach millions of people from all walks of life through his humorous and topical social media posts. He has also become an extremely effective master of the medium.

On a recent morning, for example, Takei shared a photo of a delivery truck with the words: “Driver carries less than $50 cash and is fully naked.” Above the photo was Takei’s own commentary: “That’s some discouragement.”

Within an hour, the Facebook post received more than 43,500 likes and more than 8,400 shares. On Twitter, it received close to 300 retweets in just 60 minutes. The company who owns the truck would even later post a comment on the post about openings they have for truck drivers.

The former Mr. Sulu on Star Trek says he’s as surprised by anyone that his online success has caught on like it has, but he thinks he knows why it continues to grow.

“I really do think the connective glue is humor,” says Takei, who appeals to a wide cross-section of fans, even though he may differ from some of them philosophically and politically. “Humor is what binds us all together, regardless of what our politics or phobias are.

“We as human beings are all connected by the ludicrousness of life.”