One hundred years ago, cinema was starting to change from a penny-ante novelty to the overwhelming, reality-displacing force it is today. But the technology still hadn’t progressed very far. Films in 1912, for example, still had to be shown on projectors cranked by hand.

Giving a sort of séance this week on 1912 film is Randy Haberkamp of the Motion Picture Academy, who’ll be at the Rafael Film Center on Dec. 10, along with L.A.-based musician Michael Mortilla (who just wrote a score for Hitchcock’s first film, The White Shadow) and, yes, a guy who has to stand there and turn an antique crank. Just like the old days.

Nineteen twelve was an exciting time. In Italy, Quo Vadis had been released, giving that country the honor of producing the first epic. In America, there was the first coalescing of studios, with the beginnings of Fox, Paramount and Universal. Nineteen twelve also saw the first Keystone comedy, as well as the first “urban” film, D. W. Griffith’s Musketeers of Pig Alley. The first cowboy star, Broncho Billy Anderson, was continuing his productions in the Northern California hills, including the trails around Mt. Tam.

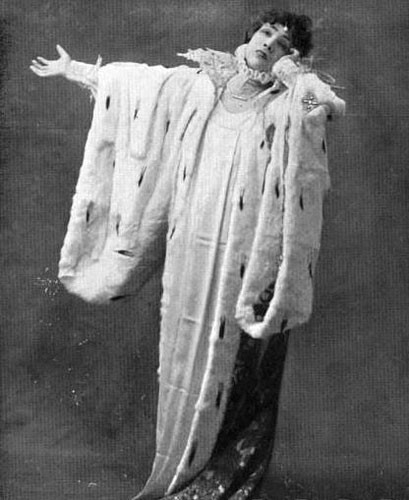

The rising power of movies at the time lured Sarah Bernhardt, the world’s most famous actress, to a four–reel biopic about England’s Queen Elizabeth, which is presented in Haberkamp’s program. The two-hour evening also includes what’s likely the first human-powered projector anyone in the area has seen. Joe Rinaudo, who has a nationally known trade in vintage-styled chandeliers and lighting fixtures in the Glendale area, will be bringing a projector that he restored himself, a device manufactured in 1906 by the Nicholas Power Company of 50 Gold St., New York.

In their day, handcranked projectors allowed traveling projectionists to take early movies out into rural hamlets beyond the power grid. But cameramen of the Billy Bitzer era cranked when they filmed, too. Projectionists thus had to duplicate the uneven speeds on their own to make sure the action looked natural on a screen.

When you see movies displayed this way, you’re mindful of the sense of exertion to create this illusion, and the trick of persistence of vision that lets movies move. The graceful yet slightly irregular motion makes these old 35mm movies look more alive—it’s rather like the surprise of watching an old film at slow speed and studying the facial expressions revealed, previously hidden by the whirl of frames we’re so used to now, 100 years after these films were made.