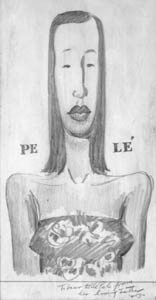

Love’s Labor Won

Petaluma artist Pele deLappe’s passionate journey

By Gretchen Giles

Possessing an uncanny knack for always being at the right place at the right time, Petaluma artist, writer, and activist Pele deLappe squeezed the best from the 20th century. Born to what she terms “nutty, bohemian” parents in 1916, she was introduced to the grossly myopic James Joyce in a Parisian cafe at age 10, took her first lover at 14, was dismissed from traditional education by her father and sent to art school before she was 15, and regularly entertained Frida Kahlo as an afterschool drawing buddy.

By 19, deLappe was already a member of the Communist Party, had seduced the great Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros and discarded him, had lived at the artist colony in Woodstock, N.Y., and was firmly ensconced in her own apartment in Manhattan. What was left for a young proletariat to do?

“Why the hell don’t you get married?” her father asked, handily supplying the candidate, a Marxist attorney who would indeed become deLappe’s first husband.

While men would come and go and often come back again into deLappe’s life, her most enduring love–beset as love affairs always are with equal parts enmity and passion–was the Communist Party. Whether petitioning the Works Progress Administration to more fairly choose artists for its plum assignments, picketing with angry longshoreman, marching with disenfranchised farm workers, or standing on a Petaluma street corner each Saturday protesting the Bush administration’s nefarious ways, deLappe’s one constant has been change, a flux that she has documented tirelessly through both her writing and her art.

Now 86, deLappe has published an autobiography, Pele: A Passionate Journey through Art and the Red Press, and has an exhibition of her lithographs, sketch books, and drawings showing through Oct. 25 at the University Library in the Jean and Charles Schulz Information Center at Sonoma State University. Professor Emeritus of Literature at UC San Diego Bram Dijkstra joins her in a special reception Sept. 13 to discuss the bloom of her youth, the art and culture of the 1930s and 1940s.

A trim, alert woman dressed against the late summer heat in a cool blouse and skirt, deLappe now lives in the art-rich apartment she sometimes shared with her “beloved comrade,” the late North Bay painter and eccentric Byron Randall. Randall and deLappe’s paths crossed many times during their lives, but the two didn’t fall madly in love until deLappe was 74. Randall died two years ago, though deLappe sometimes still speaks of him in the present tense. “It took a long time, but I finally did find my one true love,” she smiles.

The SSU exhibit is mainly concerned with the black-and-white lithographs deLappe produced during the Depression. Free to visit Harlem as a teenager, hanging out in jazz clubs sketching the musicians and patrons, visiting the freak shows at Coney Island, or documenting the poor along San Francisco’s waterfront, the artist’s cakey, voluptuous women, carefully rendered dwarfs, and sad-eyed workers possess a still, deep reverence for humanity.

DeLappe is dubbed a social realist by some for her portrayals of everyday people, but Professor Dijkstra begs to differ. Dijkstra is just finishing a book on the era titled American Expressionism. “I wouldn’t call her a social realist, as it is a false term,” he says by phone from his San Diego home. “It was invented in the ’40s to brand all this art as somehow being connected with communism. Socialist realism was considered to be the art of Soviet Russia. . . . The workers were all heroic and muscular, and the women were all blonde and beautiful and shining with happiness.

“That’s certainly not the case in Pele’s work,” Dijkstra continues. “Her realism is influenced by numerous forms of modern art, and consequently is a kind of expressionist realism. It shows the passionate concern, the emotional connection that she made to her subjects.”

No longer a party member–“We severed relations by mutual agreement,” she says crisply–deLappe worked for much of her life as a journalist for the San Francisco- based Communist newspaper The People’s World, doing everything from drawing topical caricatures to editing feature stories to illustrating essays.

“I got mad at them,” she says of the communist organization. “We’d gone through some very difficult times in relation to The People’s World being controlled by the party back East, and a lot of us found that unacceptable. The [paper] wasn’t a party organ and didn’t expound just one view. It had a labor orientation and was culturally broad.”

Her art and journalism career interrupted by child rearing and the dull necessities of making a living, deLappe was consigned for 19 dreary years supporting her family as a designer at Moore Business Forms, a job she describes as “a fate worse than death in some ways. . . . It wasn’t all negative, but it just lasted too long.”

Yet the revenge of a long life is surviving the dreariness to enjoy the good, which in deLappe’s case means remaining active and alive to the world around her.

Jabbing her finger at a newspaper story about the possibility of a war with Iraq, deLappe says, “I feel very badly that my daughter and other people’s daughters and sons aren’t having as good a time as we did. There are a lot of dead ends, and there’s this war threat all the time. It suddenly dawned on me when I read Gore Vidal’s book Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace that we have been at war since WWI. . . . Words fail me.” She shakes her head.

How has she kept her sense of urgency? Many older people choose to tune out the vagaries of the day. DeLappe will have none of it. “I don’t have a choice,” she says firmly. “I’m still alive and still part of society and still an artist. I can’t stop functioning in relation to other people.

“And,” she smiles, “I refuse to take it lying down.”

‘A Passionate Journey: The Works of Pele deLappe’ exhibits through Oct. 25 at the Jean and Charles Schulz Information Center, SSU, 1801 E. Cotati Ave., Rohnert Park. Reception with deLappe and Bram Dijkstra, Friday, Sept. 13, from 6pm to 9pm. Monday-Saturday, 10am to 5pm. Free. 707.664.2122.

From the September 12-18, 2002 issue of the North Bay Bohemian.