Rebel Radio

Michael Amsler

Local pirate-radio broadcasters are electrifying the airwaves, much to the chagrin of licensed stations

By Dylan Bennett

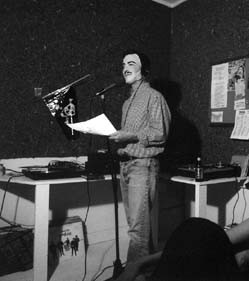

Frank Black’s radio program has it backwards. Instead of brief talk segments punctuated by commercials, news, and station identification, the Frank Black Cocktail Party on West Pole Radio (88.1FM), features about 30 minutes of wide-ranging, irreverent conversation interrupted by a few underground pop songs, followed by another long rap session. The signal from this illegal 12-watt transmitter, located in a hush-hush studio on the edge of Santa Rosa, reaches only about 10 miles. But given the luxury of time, Frank Black chews on some big subjects.

Like oral sex.

“That’s disgusting,” says Black flatly, standing at a microphone beside a table full of audio gear. “If a girl absolutely insists I go down there I will, but I won’t stay a second longer than I have to. It’s not clean, man. I mean, I don’t want to get sick. It’s not healthy.”

Is this man crazy or just kidding?

Ask Black’s guests. On this evening, they are the Wind Goddesses, that’s Star and Venus. And they’ve come to counterbalance just this kind of chauvinistic pap coming from Black. “Frank is coming from a place of paranoia and fear,” concludes Star. In the one-room studio, the guests sit on an old lumpy couch, wearing sensual loose dresses. Flowers adorn their cascading black and auburn hair. The air in the cramped, closet-sized studio is a little stuffy, but the atmosphere is warm and familiar. Sitting next to Star is Black’s sidekick, Cougar, a hard-bodied young jokester not far out of high school. Monkey Boy sits on the floor against the wall and chimes in whenever the topic gets boring or strays too far afield.

At the moment, that’s not a problem. “The problem is most men don’t know what a woman likes,” says Star. “They use their tongues like some sloppy washcloth. The clitoris is stimulated by consistent, gentle pressure. So don’t change what you’re doing when she starts to like it.”

There are no commercials, but this definitely isn’t National Public Radio.

Because West Pole is pirate radio, Frank Black commits a federal crime by broadcasting without a license. Borrowing the local nickname for the small west county town of Occidental, the station began broadcasting from a clandestine Sebastopol location in January and moved to Santa Rosa last month.

Other pirates have operated in the Redwood Empire over the last year, and West Pole’s emergence in Sonoma County’s largest city marks the local ripening of the nation’s most dynamic and democratic trend in mass media. West Pole is one of an estimated 500 to 1,000 low-power radio stations operating illegally in the United States, broadcasting to local listeners without the sanction of the Federal Communications Commission.

The result is an unregulated, radically populist medium that provides a platform for common citizens to distribute their politics and culture to their own neighborhoods and beyond.

The movement provokes no uncertain opposition from the FCC and the National Association of Broadcasters. Radio pirates universally regard these two agencies as the bad guys. The FCC, they say, is the government enforcer of that monopoly rather than a fair regulator of the public airwaves. The NAB is an influential lobbying organization for the mostly corporate broadcast industry that pirates believe hold a monopolistic cartel over the radio dial.

Across the country, free-radio stations are known to broadcast everything from working-class and environmental politics to high school football games, city council meetings, and interviews with political candidates. Such stations serve housing projects, small towns, rural counties, and big-city neighborhoods. The pirate community cuts across ideological lines, and includes a network of Black Liberation stations and plenty of conservative Christian radio as well as extreme right-wing elements. And as at West Pole, pirates typically broadcast an eclectic mix of music not found on the current hit parade.

In California, pirates flourish and skirmish with the FCC in San Rafael, San Francisco, Fresno, San Jose, Santa Cruz, and Salinas, beaming out left-wing politics to folks in Berkeley, traditional Latin music and labor politics to migrant workers in Salinas, new history in Lake County, and bilingual programming in San Francisco’s Mission District.

In addition to West Pole, Sonoma County is home to several other self-styled underground radio stations, including River Rat Radio in Monte Rio and KSRF 96.9FM in Sebastopol, run by local teenagers on the weekend. Others broadcast in Petaluma, Bodega, and Rohnert Park. West Pole Radio runs from 5 p.m. to midnight on weekdays, but many pirate stations operate on unpredictable schedules–and frequencies–to elude detection.

“Our plan is to push the limits of pirate radio as far as we can get away with,” says Black. At first, West Pole doesn’t appear to push the limits very far. Black and his collaborators say they are not political. They don’t use their real names. Programs like co-founder Brown Jenkin’s Bachelor Pad, featuring “beer, bikes, and music,” don’t seem like much of challenge to the status quo.

Yet, in that instance, the music is fiercely independent, underground rock, funk, and jazz; the bicycles are a new ethic in transportation. Even the Frank Black show, in its ongoing exploration of “the mysterious mating rituals of human beings,” confronts a vital menu of social politics, poses prickly philosophical questions, and talks openly about sex and drugs.

Black, while often indulging in cheap male belligerence, is actually a skillful journalist. He forces listeners to evaluate their own thoughts. Isn’t the schoolboy who sleeps with his teacher just getting lucky? Is the journalist who distributes child pornography while infiltrating that underworld industry to get the scoop guilty when he’s caught in a police sting?

“This Frank Black character, this alter ego, is just an expression to entertain people but bring somewhat serious topics to the light,” says Black. “But I do it in a humorous manner to get people thinking about certain things that are, for the most part, taboo subjects, or subjects that aren’t discussed but should be discussed.”

Unlicensed broadcasting is a federal crime punishable by a year in jail and a $100,000 fine from the FCC. So how are so many people getting away with it?

Low-power radio transmitters are small, portable items about the size of a textbook. They are the most affordable form of mass media. For as little as $500, a station can get started, and for an average of $1,500 pirates can broadcast over a 10-mile radius. This availability lends a powerful organizing tool and political forum to even the most poorly funded voices of opposition and activism.

“It’s a low-tech crime with old-school technology,” says Black, who thinks the chances of getting busted are nonexistent. By strength of numbers, pirate stations constitute a guerrilla media army performing electronic civil disobedience in open defiance of the existing law and commercial media.

Pirates call on a higher law of free speech, he adds, due process, and fairness under the law.

“I have vowed to put 10 stations on the air for every one the FCC shuts down,” says Stephen Dunifer, founder of Free Radio Berkeley and unofficial figurehead of the free-radio movement. “The government doesn’t have the resources to shut everyone down.”

To meet his goal, Dunifer markets a catalog of low-cost products needed for setting up a microradio station.

In California, all eyes are on the FCC’s bellwether case against Free Radio Berkeley. Last November, federal Judge Claudia Wilkin rejected the FCC’s latest request to shut down the station that Dunifer started five years ago. Until the case goes to trial in a year or two, some consider unlicensed low-power broadcasting to be virtually legal.

“It’s not illegal until Dunifer goes to trial,” asserts pirate broadcaster Bonnie Perkins of Lake County Radio (88.1/90.3FM). For her weekly program, titled “Censored History,” she proudly says that some locals call her “the Noam Chomsky of Lake County.” Perkins, a self-described “housewife,” says, “Nobody has been touched since the Dunifer case–in California.

“They hit in Arizona and Florida, that we know of. They were horrible raids. [The feds] destroyed everything, just like in Waco.”

Well, not just like Waco, and pirate radio is not exactly legal.

FCC spokesman David Fiske says any notion that unlicensed broadcasting is legal is “simply not true.” The FCC starts with warning notices, followed by seizure of equipment and fines. Ninety pirate stations “voluntarily” shut down in 1997, after receiving warnings from the FCC, and seven were physically closed by federal marshals. In several cases in which pirates have refused to turn off the mike, FCC policy has translated into a SWAT-like team with machine guns bursting through the front door.

Last November in Tampa, Fla., heavily armed cops reportedly busted down the front door of radio pirate Doug Brewer’s house, held Brewer and his wife on the floor at gunpoint, seized his equipment, and ransacked the house. “I had absolutely no political agenda–at least not until they came in here with guns,” Brewer told the Los Angeles Times. “I just thought Tampa radio sucked and we had to do something to improve it.”

This year 65 stations have closed after getting warnings, according to the FCC. Arthur Kobres, also of Tampa, was convicted in late February on 14 counts of broadcasting without a license. He faces up to 28 years in jail and a $3.5 million fine. His conviction is thought to be the first of its kind in many years.

At the center of the free-radio world is Dunifer, a self-described anarchist, member of the radical Industrial Workers of the World, and a veteran of resistance politics, from the Vietnam War to old-growth redwoods. A tireless crusader for free radio, Dunifer manufactures and sells transmitters from his home, and offers assistance to all comers, including communities in Mexico and Haiti.

Dunifer found his inspiration in such pirate radio pioneers as Mbanna Kantako, a legally blind man living in a Springfield, Ill., housing project who started broadcasting Black Liberation Radio in 1987 on a one-watt transmitter. At first ignored by the FCC, Kantako was fined $750 and found himself the subject of harassment after he addressed police brutality in Springfield. Regarded as the father of the microradio movement, Kantako still broadcasts Human Rights Radio in Springfield.

In the early days, the 46-year-old Dunifer on occasion transmitted from a car, sometimes even a backpack in the Berkeley hills. He wears long straight gray hair, a foot-long beard, glasses, and a blue denim jacket. He shakes hands gingerly because of a degenerative form of arthritis, but he speaks with the strength of deep conviction.

“The status quo is the corporatization of our lives, like when a kid gets kicked out of school for wearing a Pepsi shirt on Coke Day,” Dunifer recently told a Sonoma State University media law class at which the students were peppered with Nike logos. “The yoke of the new feudalism sits on the neck of every person on the planet.”

Behind the battle between the pirate radio and the FCC lies the core issue of media ownership. Free-radio advocates argue that the concentration of media ownership in the hands of just a few giant media conglomerates, along with the enormous cost of licenses, makes broadcast media the exclusive activity of the very rich.

“The FCC has raised the barrier so high that only the wealthy and well-endowed have a voice,” argues Dunifer. “The real pirates are the corporations who stole the airways. At the very worst, we can be portrayed as attempting to return stolen property.”

In April, at the NAB’s Las Vegas convention, Louis Hiken, one of eight attorneys providing pro-bono services to Free Radio Berkeley, presented a position paper titled “Broadcasting, the Constitution, and Democracy.”

Notes Hiken: “Let’s look at radio, the media sector most thoroughly affected by the recent Telecommunications Act. The act relaxed ownership restrictions so that one company can own up to eight stations in a single market. In the 20 months since the law came into effect, 4,000 of the nation’s 11,000 radio stations have changed hands, and there have been over 1,000 radio company mergers. Small chains have been acquired by middle-sized chains, and the middle-sized chains have been gobbled up by the few massive companies that have come to dominate the industry.

“This sort of consolidation permits the giant chains to reduce costs by downsizing their editorial and sales staffs, and running programming out of the national headquarters. According to Advertising Age, by September 1997 in each of the 50 largest markets, three firms controlled over 50 percent of advertising revenue [and programming]. In 23 of the top 50, three companies controlled more then 80 percent of the ad revenues. CBS alone has 175 stations, mostly in the 15 largest markets.”

Ben Bagdikian, author of Media Monopoly, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, and professor emeritus at the UC Berkeley School of Journalism, says that 12 major corporations dominate the mass media, down from 50 just a few years ago.

“The significance of the whole movement of the pirate stations is, while it is obviously against the law, a symptom of the failure of the FCC to demand of local stations that they allot a certain amount of time to local groups,” says Bagdikian. “And they used to do that. In the last 30 years or so they have failed to do it.

“The present trend is to worsen things,” he adds, “moving toward more and more consolidation of national chains in radio. More and more limitation to a few fixed formats that have very little place for local access. And especially in the major markets. Local community groups, including quite significant ones–ethnic groups, civic action groups–have almost no access to those stations. And that used to not be the case. It used to be that if you had a radio license, or a TV license for that matter, when the renewal time came up, the FCC wanted to know how much you had served your own community.”

Dunifer agrees. “Mainstream radio does not reflect diversity,” he says. “Microradio is very diverse, which speaks to the whole issue. The great appeal is the culture to be expressed. People gravitate to it because the regular outlet is denied. Microradio is not just a bunch of crazy anarchists from Berkeley, but an incredible diversity that promotes civil discussion across the spectrum of ideas.”

FCC officials say that pirate radio endangers the public by interfering with aviation and public safety frequencies; and that pirates interfere with licensed stations and don’t participate in the Emergency Alert System.

John Earnhardt, spokesman for the NAB, representing 5,000 radio stations and 12,000 TV stations, echoes the FCC policy concerns about air traffic safety and frequency interference. “It’s serious,” he says. “Not just because it’s illegal, but because it gets to putting some lives in danger.”

Mitch Barker, p.r. representative of the Federal Aviation Administration, says the FAA has documented five cases of interference with aviation frequencies, including a Sacramento case in which a poorly constructed transmitter interfered with airplane traffic. The FCC’s Fiske says an airport in Puerto Rico was nearly forced to shut down owing to extensive interference before authorities nabbed the guilty pirate station.

In Seizing the Airwaves: A Free Radio Handbook, edited by Dunifer and Ron Sakolsky, Dunifer agrees that interference is a legitimate concern and explains how pirates can study their local radio dial to avoid interfering with traffic control signals. Usually, he says, there are plenty of available slots in the radio spectrum to accommodate low-power community radio. “The whole point is to be a community asset, not a community nuisance,” says Dunifer. “It’s ludicrous for the FCC to stand in the way of a community to start its own voice for $1,500.”

In Sonoma County, licensed broadcasters express mixed feeling about rebel radio outfits like West Pole Radio. “If it’s one or two stations it’s not relevant, because there are 60 choices on the dial,” says Lawrence Amaturo, whose family owns local stations KMGG, KXFX, KMGG, KFGY, and KSRO, and two more radio stations in Southern California.

“But if it’s 20 stations,” continues Amaturo, “it becomes very relevant to our ability to maintain a level of quality because our revenues would be measurably impacted by that sort of proliferation. Every broadcaster in this town works extremely hard, and we have the privilege of serving our community–and a responsibility. Pirate radio has none of that. It’s just about themselves. They just play what they want. They’re not constrained by any FCC regulations. They have no watchdog to watch for them broadcasting inappropriate material.

“And that’s problematic.”

Brent Farris, the gregarious vice president of programming for KZST, spoke, along with Dunifer, to the SSU media law class. “I’m very sympathetic to pirate radio,” says Farris, noting his credentials as a former practitioner of “free-form hippie radio” in the 1970s. “My only concern is that anybody can do it. Which means that the people with good intentions can do it and the people with bad intentions can do it. That’s why you regulate it. Doesn’t matter if you’re right-wing, left-wing, fanatic, conservative, liberal. Does that scare you? It scares me.

“And I believe in free speech.”

At KRCB public radio, program director and acting station manager Robin Pressman considers the non-commercial station to be a pirate station with a license. “I certainly understand the movement because of what’s happened in the world of radio, the conglomeration of radio stations, so that something like eight companies own all of the radio stations in the United States,” says Pressman. “There are very few locally owned stations anymore. [The big companies] are ruining radio in dictating play lists from a central office so that the same things are being played on every radio station. It’s a very narrow band, what’s available… .

“We are definitely simpatico with the people who are doing pirate radio.”

But Maria Fincher, station manager of Santa Rosa’s KBBF-FM–the first bilingual public radio station in the nation, now celebrating 25 years on the air–opposes the pirates on principle. “I don’t approve, because you have to find the right channels and follow the rules. I’m public radio. And I don’t have the money that commercial radio does. I can’t do the things they do. If I can’t do that, then I just can’t do it.

“I can see their point, but it’s an easy way to get what you want.”

Media law attorney Hiken has proposed that low-power stations be allowed to occupy unused frequencies, formally register with a simple application form, keep their signal under 50 watts, and follow basic technical criteria. His proposal envisions one station per organization, no commercial sponsorship, and no content requirements.

Such calls for the legalization of low-powered community stations appeals to some at Lake County Radio. However, the diversity of the movement also imprints itself on this question. “The day we have a license, we won’t be able to do any of this,” says Frank Black.

I don’t think that’s the route to take,” says Bagdikian. “The necessity is for the FCC to take cognizance of the fact that low-powered stations have a real community function and that there should be a demand that stations provide significant time to local groups. What I hope is that the legal cases of the pirate stations, whatever their outcome, will dramatize the fact that, though they’re illegal, they reflect a need that the government has not provided.”

Meanwhile, at the new West Pole digs, Black enjoys a little elbow room, even a window, and a growing list of sponsors: Punch Street Wear, Flying Goat Coffee, Slice of Life vegetarian restaurant, Bohemian Cafe, Box Office Video, and Village Bakery.

Apparently somebody is listening.

“I think they’re doing a great thing,” says David Burns, owner of Slice of Life. “There’s room and a need for people doing things like that. There’s a lot of people who have some good information and other, alternative types of entertainment that would never ever be heard because not everyone can afford an FCC license. Why just leave it to all these people with big corporate bucks?”

From the May 14-20, 1998 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.

© Metro Publishing Inc.