Raymond Barnhart has an affinity for the unusual

By Gretchen Giles

This article originally ran in 1996, in conjunction with a major retrospective of Raymond Barnhart shortly before his death. Barnhart was a major influence on a number of North Bay artists, including Kurt Steger, whose work is now on exhibit at the Sonoma Museum of Visual Art.

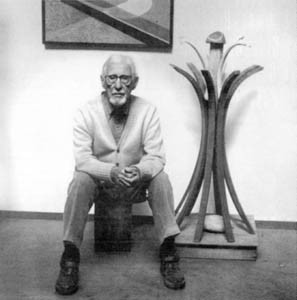

Rock, feather, stone. Shell, glass, wood. Skull, bone, and skull bones. These are some of the elemental objects that Sebastopol artist Raymond Barnhart, 91, gathers to create his assemblages, using them to transcend their original form, using them to honor their past. By now we’ve all been New-Aged to death by artists who find a muddy profit in natural objects. Mother Nature has gone commercial; you can buy her at the mall. However, Raymond Barnhart is not just some old man who found a pretty shell, tacked it on to a piece of driftwood, and voila!–$34.95. Barnhart is the real thing. He is an artist with a huge career behind him, exciting work before him, and a collection of pieces that are stunning in their simple complexity.

“Raymond Barnhart: A Chronological Review,” now at the California Museum of Art in Santa Rosa, traces Barnhart’s career from an adolescent pen-and-ink drawing composed in 1913, to his years as a painter and professor at the University of Kentucky, to his transformation into an assemblagist, a maker of profound three-dimensional collages created from found objects.

Barnhart’s career has almost spanned the century, his work influenced by the Bauhaus master László Moholy/Nagy, color deconstructionist Josef Albers, and painter José Gutierrez, who developed acrylic paint. He has traveled all over the world, setting up studios on-site in foreign countries and obscure parts of this country, and lived for months in Europe in his VW van (when he was in his youthful 70s). He has seen the world, touched it, unearthed it, yanked it from dust and abandoned buildings, and brought it home.

Speaking by phone from his west county home, Barnhart explains a little of what it was like to be involved with the movements of his youth. His voice is rough and aged, but his ideas are not. Barnhart speaks with the meticulousness of an academic, carefully spelling names and pausing politely to ensure I get it all.

“The idea was how to make things by getting acquainted with the materials and following the demands of the materials,” Barnhart says of his work with Moholy/Nagy. “We would study things in a very fresh sort of way. It was a matter of discovery by examining the material freshly all over again and determining what the material wanted to do.” This is exactly what Barnhart has done, particularly with his later work.

This show starts young and evolves with the vision of the maturing artist, as Barnhart’s mediums and ideas changed. The paintings show a range of styles and influences, from still lifes to a Dali-like perspective piece: the work of an alert restless mind trying different things. Barnhart is less than pleased about the shortage of space available to show his early work.

“Of all the paintings you see,” he says, “that’s only one of many many things that I did. It looks as though I just jumped around. I didn’t, but I would need a room four times that size to show them correctly.”

While the paintings are pleasing, and an important key to his later work–which, though no longer involved with canvas retain a painterly manner, examining color and often boxed into an organic frame, held tightly by the beautiful weathered wood that is one of Barnhart’s passions–the whole exhibit stops short and explodes with the assemblage works.

“A lot of my work has to do with things that just happened,” says Barnhart. One of his latest pieces has been brought to the museum from his garden. It’s a long, weathered piece of wood draped with a Japanese print, and aligned along it is a pitchfork collaring a bone and holding in its tines an abalone shell topped with a crown of thorns. Of this piece, which is untitled, Barnhart says,” I respond to the possibilities that I get from the objects. I picked up this wonderful pitchfork that I found years ago on a trip to New England. I set it in the hallway, and I had this pelvic bone and I found that they hooked together. The Japanese script was unintelligible, and it kind of kept the whole thing a secret, you see.” The crown of thorns was picked up years ago after a religious procession in Mexico, and the shell “happened to have a hole in it.”

Barnhart’s home and studio are cluttered with beautiful castoffs that he pairs in an attempt to create a new harmony among disparate objects. “These things come together a little bit at a time,” he says. “I have several going at once.” If one piece isn’t working, he lays it aside until he lights upon an object or an idea that will effect a cohesion within the piece. His work is created from the respect he has for his found objects, and the sense of each object’s own destiny, “a psychological appreciation of what it has become.” One leaves his show feeling deeply refreshed, sluiced by the minute harmonies he has wrought.

Co-curator Gay Shelton says of Barnhart’s work, “What he does is so simple, but so deeply seen.” Yes.

From the January 18-24, 2001 issue of the Northern California Bohemian.