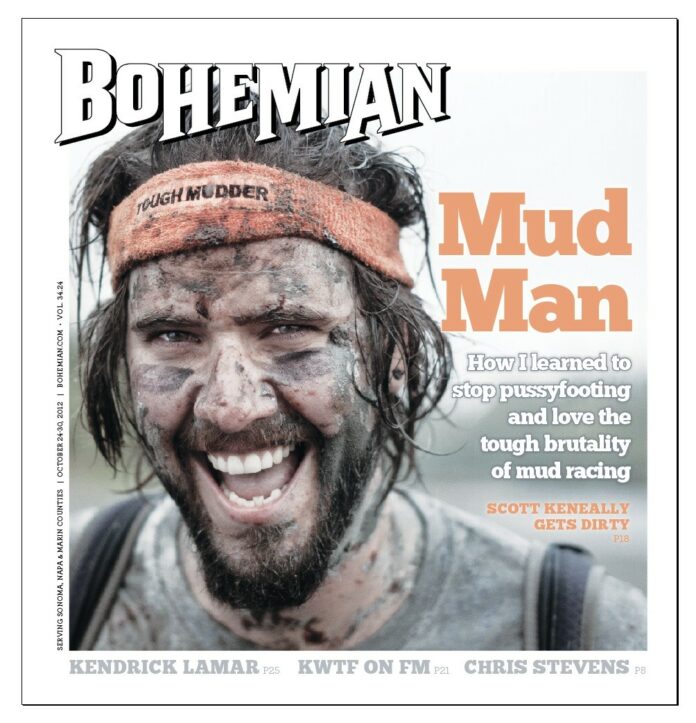

See that guy there? The one wincing? That, dear reader, would be me—a hundred feet from the Tough Mudder finish line last fall. You’d think that after enduring two-dozen military-style obstacles over 11 miles of high-altitude hell at Squaw Valley, I’d be thrilled to be so near the end. Instead, I’m locked in a full-body cringe, terrified of the curtain of electrified wires that hang between me and a free Dos Equis. “Electroshock Therapy,” with its promise of a 10,000-volt jolt, is the obstacle I’d most feared. And that right there is the pained expression of a man wondering, What the fuck am I doing here?

Maybe this wasn’t such a good idea after all. Especially for a guy like me.

If you haven’t heard about Tough Mudder or read about it or at least seen Facebook pics of your friends doing it, here’s a quick snapshot. It’s a 10- to 12-mile mud run that employs extreme obstacles like ice, fire, electricity and barbed wire to sensational, almost sadistic effect. And it’s insanely popular, with 35 events in 2012 that, by year’s end, will have drawn an estimated 500,000 Mudders and $70 million in revenue.

I’ve never thought of myself as particularly tough. While I was one of the biggest guys on the football squad during my senior year in high school, I was also one of the softest. Whereas Tommy Tremarco and Anthony Cacase played with casts covering broken bones, I’d sometimes ask to sit out wind sprints because of “chronic shin splints,” a self-diagnosed condition. “Maybe if you’d actually hit someone instead of just pussyfooting around all the time,” said one coach, “your shin splints would go away.”

These people all thought me a pansy, though I preferred to think of myself as pain averse. Regardless, not much has changed in the years since. I’ve been known to sniffle at Applebee’s commercials, cry while watching The Voice, sob during Glee and squeal at the sight of spiders. When writers write about the death of the American male, they’re writing about me. Which, incidentally, is why I was so shocked by what happened after watching my first Tough Mudder promo video.

At first, I was mortified by the montage of obstacles “designed by British Special Forces.” Just watching it made me want to pop a Vicodin. But there was something disarming about seeing all the costumed crazies conquering the course. Tough Mudder, with its festival atmosphere and countercultural vibe, seemed to be doing doughnuts at the intersection of fun and fitness. It looked exactly as promised: “Ironman meets Burning Man.” And its motto—”Probably the Toughest Event on the Planet”—was a call to arms for the alpha inside. So without pause or ponder, I decided right then and there to run the next NorCal event, just three months out.

Never mind that I hadn’t seen the inside of a gym or run 10 miles—total—in the previous three months. That video and the many others I watched flipped a switch, and for the first time since I realized that a career as a linebacker for the New York Giants wasn’t in my cards, I trained as if it were. I ran. I set daily pull-up goals. I did side planks during commercials. And I spearheaded a few healthy initiatives I’d largely avoided. Like eating greens. And drinking less. I thought about going raw, but then I realized I had no idea what the hell I was talking about.

This was all welcome news to my super-fit wife, Amber, of course, a personal trainer who serves as the yin to my sin. I became a regular at her circuit-training classes, even though said classes seemed largely designed to make me puke. I got stronger, strengthened my core. I got to the point where I could do a plank for 30 seconds without my whole body shaking like a Magic Fingers mattress. I ran the same Lake Sonoma loop, five miles a day, day after day, and kind of started loving it. I did interval sprints up steep trails, and sometimes screamed “Fuck yeah!” at the top. I was a man on fire.

But I knew Mudder wasn’t just about strength and stamina; it was about mental toughness and grit. And since I will stop a trail run dead in its tracks to pick out even the tiniest pebble in my sock or shoe, I knew I needed to harden up in a hurry. I needed to steel myself like Rocky Balboa might, so I started agitating my routines. I swam in the lake with my sneakers on. I ran up fire roads with stones in my toes. And in anticipation of the ice water obstacles, I took cold showers every once in a while. (Well, maybe just once—but it was for a good 20 seconds or so.)

Slowly but surely, bit by bit, I amassed a thin layer of grit, which I tried to shellac with a viewing of Rocky IV the night before the race.

[page]

I rented the flick in hopes of psyching myself up. I felt that familiar adrenaline flash when Rocky went to Russia to fight Ivan Drago. In fact, I was so worked up by the Vince DiCola-scored training-montage scene of Rocky running through snowdrifts that I wanted to charge the course that night. Tough Mudder was my Drago, and I wanted to take the evil S.O.B. out. Unfortunately, however, the intoxication didn’t last long. In the very next scene, when his wife Adrian shows up unannounced to support him, I started snot-bubbling so fervently you’d think I was watching The Notebook. My hard-won mental grit was now crumpled up in Kleenex. I had a long way to go, obviously, but there was no time to go anywhere but sleep.

By some strange magic, I sprang out of bed the following morning full of confidence. I dropped down for 20 pushups, beat myself in the chest for effect and declared to the man in the mirror, Today, I will be William Fucking Wallace. And I meant it. This vibration intensified upon arriving on the scene, spiked when I signed my death waiver and reached a fever pitch while reciting the Tough Mudder pledge in the starting corral. “I will not whine—kids whine!” we chanted, though within moments of the gun going off, as we began the steep, initial ascent, I found myself looking longingly at the gondola. Who would know?

Twenty-five lung-busting minutes later, after dragging myself in a mud bog beneath barbed wire, I came across one of the most dispiriting things I thought I’d ever seen: the first mile marker. “MILE ONE,” it announced, simple and direct, like a middle finger. Panic rushed forth: I’ve got 10 more miles of this?

If there was one thing that set my mind at ease, however, it was the camaraderie on the course. It didn’t feel competitive as much as collaborative, reflecting the pledge, “I understand that Tough Mudder is not a race but a challenge.” And true to word, Mudders were always helping other Mudders out. Most people were not concerned with their course times, like the “Gockasauras” team that carried an inflatable T. rex. This was just fine with me, as I couldn’t run up the hills at this altitude anyway. Instead, I adopted a run-when-I-can strategy, picking my spots and pacing myself, which, if I’m being honest, is another way of saying that I only ran when the trail was level or going down.

Of course, the obstacles are the big sell here, and while they weren’t all “tough,” they were all uncomfortable. Some, like carrying logs, were physically taxing. Others, like crawling through tunnels filled with rocks, were just annoying. And a few were kind of depressing, like the monkey bars that illustrated just how little upper body strength I have. But the worst ones for me were the cold ones.

The shock of leaping from a 12-foot platform into a snowmelt pond, for instance, left my head feeling like I’d just mainlined a milkshake—though it paled in comparison to “Arctic Enema,” a plunge through a dumpster filled with slushy ice water that taught me the difference between a simple brain freeze and a full skeletal shudder. That paralyzing cold was hard to kick, too, since I had no chance to move around and warm up before walking up to an obscenely long, 30-minute bottleneck at the next obstacle, “Everest.”

[page]

Still, I felt like there was nothing on this course I couldn’t handle. Until the seven-mile mark that is, when my knee nearly buckled in stabbing pain. I didn’t know this at the time, because I’d never heard of an IT band, but I was sure that with each step, some tendon or muscle—something—was sawing into the lateral part of my knee. The intense friction made it difficult to put much pressure on it, forcing me to limp when the trail was level, and lock my good knee and skip when descending. I knew it looked graceless (at best), like I was galloping on an invisible broomstick, but for once in my life I had little bandwidth for vanity. I just wanted to cross the finish line on my own two feet. And though the final four miles went by excruciatingly slow at times, as I limped, lurched and skipped forward, I’m sure that when I arrived at “Electroshock Therapy,” I forgot all about the knee.

I didn’t know what 10k volts felt like yet, but after watching dozens of YouTube clips of people face-planting in the mud and hearing the screams of those ahead of me, I knew it wasn’t going to be a party. Some people slowly needled through, careful to avoid any wires, while others crawled beneath reach. There was a rumor going around that once a wire was triggered there was a refractory period while it recharged. If the theory held, you could avoid getting shocked by running behind someone. But none of those options seemed appealing.

As I stood there, pondering how to best attack this final challenge, I realized that I secretly wanted to get shocked. I didn’t want to willingly shortchange the experience. I’d come all this way, and at the end of the day, as much as mud runners love showing photos of themselves looking like Navy SEALs at these events, we love telling you all the gory details. And let’s face it, the story about how I deliberately avoided getting shocked just doesn’t woo at the water cooler as much as the one about the moment of impact.

This is what I told myself, at least—over and over—until finally summoning the courage to charge ahead. And while I may look less like Rambo in this pic, and more like the Boy Who Cried Shin Splints, as I left Squaw I knew I’d earned something I didn’t have before charging into the fray: the pride that only comes when you can look yourself in the mirror and say, Today, I WAS William Fucking Wallace.

—

The Dirty Race

Is Tough Mudder an entirely clean company?

Last fall, I journeyed to Tahoe with hopes of writing a funny, experiential essay about doing my first Tough Mudder. After reading up on the company, however, I chanced upon a riveting scandal in the comments sections of various news stories, blogs and YouTube clips: Tough Mudder was being slammed for stealing the idea from the Tough Guy Competition, a popular obstacle race in the U.K. What’s more, they claimed that Will Dean, Tough Mudder’s 31-year-old CEO, did so while studying for his MBA at Harvard.

I wasn’t exactly sure where this would lead, but I dove headfirst into the mud pit anyway, and by some magic or miracle, I sold the pitch to Outside magazine. After a year of research and reporting, writing and rewriting, my 5,600-word investigative feature about the scandalous origins of Tough Mudder is its November cover story, on stands now. Given the CEO’s Harvard pedigree, and the popularity of his company, the exposé has garnered widespread attention and generated headlines, including in the Huffington Post, which asked, “Is (Will Dean) the Mark Zuckerberg of Mud Runs?” You can find the story on newsstands now, or read it online, but in the meantime, I wanted to take this opportunity to share the story I initially set out to tell—the one about Tough Mudder and me.—Scott Keneally