Nothing says North Bay like a world-class, Grammy award–producing recording studio built on an old 10-acre chicken ranch. At Prairie Sun Recording Studio in Cotati, vintage analog gear and state-of-the-art digital equipment coexist in buildings that used to incubate chicks and store grain. Transformed by founder Mark “Mooka” Rennick in 1980, Prairie Sun has welcomed the biggest names in the industry to this ranch location and has become renowned in musical circles and mythologized by Sonoma County locals.

As a music fan and Sonoma County native, I had heard countless stories about the place and had to get a look at Prairie Sun for myself. After passing the driveway twice (there’s no sign on the rocky rural road advertising the studio’s location), I greet Rennick in the parking lot, a sly smile on his face and two ranch dogs at his side. The 64-year-old’s silver hair sways in the breeze as he offers me his hand. “Welcome to Prairie Sun,” he says with a slight Midwestern drawl. “Ready for the tour?”

The rural site houses three separate studios and two farmhouses where local and out-of-town bands come to stay, like a music summer camp, while they work all hours of the day. In the last 30-plus years, Rennick and the staff have hosted performers of every conceivable genre, from Arlo Guthrie to Iggy Pop, and have recorded everything from Tibetan singing bowls to a Sonoma County forensics team.

STUDIO C

Rennick brings me into Studio C first, an old egg-incubating room. Now a large echo chamber largely used to track drums, the studio features a mural painted by Tubes’ drummer Prairie Prince that resembles the fields of Rennick’s youth, where he grew up in Galesburg, Ill.

“So this is the Prairie Room,” says Rennick, who took the name Prairie Sun from the student newspaper at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and the Prairie Grass Restoration Project, which Rennick worked for in his youth. “This is a prairie story in Sonoma County.”

Prairie Sun Studio manager Nate Nauseda meets us there. With sandy blond hair and a Superman-cleft chin, the 27-year-old Nauseda doesn’t look like a guy who was up until 3am recording the night before, although that’s exactly what he was doing, nailing down a bass part for Sonoma County trio Rainbow Girls. The two immediately start swapping stories with each other.

“We had Kiss’ drummer in here [in 1983],” Rennick says. “That was a big moment. Faith No More did their first record here. Testament did their first record here.”

“Stuff like Racer X, stuff on the Shrapnel [Records Group],” adds Nauseda. Formed in 1980, Shrapnel is a Bay Area label dedicated to heavy metal. Rennick guesses that Prairie Sun has done at least a hundred of their releases over the decades.

Other big names that have come through the studio include Van Morrison, Booker T. Jones, Carlos Santana, Dick Dale, the Doobie Brothers, Gregg Allman, Johnny Otis, the Melvins, Primus and Les Claypool, Wu Tang Clan, the Mountain Goats, Delta Spirit and AFI. “You do this for 40 years,” Rennick says, “who hasn’t recorded here?

“We just had a reggae band here, Jah Sun and his backup band the Dubtonic Kru,” he continues. “So we had an entourage of, like, nine Jamaicans and an Italian production team and their wives, cooking Italian food and talking Rasta. It was fascinating.”

That’s the beauty of Prairie Sun. Bands from around the world come in, stay as long as they need and bask in the communal vibe of the place.

The studio also owns any and all gear one would need—dozens of guitars, drums, a 1914 Steinway grand piano and everything in between—as well as both analog and digital recording equipment that’s run by a team of expert engineers, all in service of the artist.

THE WAITS ROOM

“It’s a really interesting room, because it should not sound good,” says Prairie Sun chief engineer Matt Wright as we step into a bare-bones storage room just off Studio C, known as the Waits Room. “It’s a cube, which violates all the rules of acoustics. But something about the cement floor and the bare wood walls—they’re paper thin and not nailed down in very many spots, so it vibrates.”

In 1989, after relocating from Los Angeles to Sonoma County, songwriter Tom Waits was looking to do something new. “Tom Waits wanted to do a record here, but he wanted something radically different, sonically,” Rennick says.

At first, Waits wanted to bring Prairie Sun’s gear to his own basement. Then he happened upon the room, little more than a closet and less than 200 square feet, which he stripped out, settled into and recorded in, most notably his critically acclaimed album Bone Machine. In a 1993 interview with Thrasher magazine, Waits said, “I found a great room to work in, it’s just a cement floor and a hot water heater. . . . It’s got some good echo.”

“It really serves acoustic music, anything that should feel organic,” Wright says. “It sounds like someone’s living room.”

“If you listen to Bone Machine,” Rennick says, “you can really hear this space.”

“It’s a character on those recordings,” Nauseda adds.

“And now it’s a shrine,” Rennick says.

Wright, nodding, says, “It’s a pilgrimage for a lot of musicians.”

These days, bands like Royal Jelly Jive and Brothers Comatose come to the Waits Room to record and pay homage. Royal Jelly Jive’s recent release, Stand Up, even features a song called “Dear Mr. Waits.”

Last year, Oklahoma’s Turnpike Troubadours stayed a month on the property and recorded their self-titled album largely in the Waits Room. That album reached No. 3 on the Billboard country chart. Critics praise the album for its intimate sound. In an interview with PopMatters last year, bassist RC Edwards said, “We’ve never had that kind of time in the studio before, just to get in there and feel like the pressure was off. We could take our time, try new ideas and just get really comfortable. That’s by far the most comfortable I think we’ve ever been in the studio.”

[page]

BOYS AND THEIR TOYS

“What it is, is we’re gear whores,” Rennick says, “and we’re not ashamed to say it.” He leads me over to a massive board, an early-’70s Neve console, one of two on the property.

“It’s still the recording desk,” Wright says. “It’s bigger than life.”

Gearheads may know the name Rupert Neve, but the rest of us? Suffice to say he’s one of the most preeminent designers of recording equipment of the last century. He began his career building radar equipment during WWII and has spent a lifetime as an electronic engineer developing and evolving mixing boards and consoles. Neve just turned 90 and lives in Texas.

Other highlights of Prairie Sun’s gear list include the console that the Who recorded their 1973 rock opera Quadrophenia on and several vintage Studer two-inch, 24-track tape machines that are in good condition. The studio also has dozens of vintage guitar amps, four drum kits, 60 to 70 electric and acoustic guitars and a locker full of every kind of microphone under the sun.

“I think people are excited about working in recording studios again,” Wright says. “People thought the DIY thing was a permanent shift, but it was a moment in time. And it wasn’t just music—people thought the way to do everything was to do it yourself.

“Now most of the bands I know hire professionals,” he continues. “The bands are no longer trying to do it all themselves. And a lot of it has to with the fact that they don’t have time. If they’re serious about their music, they have to spend their time booking and performing. And they’re also excited about the craft of records—they’re record fans. They’re excited about making albums as a piece of art, the way their heroes did, and they want to do it in the same type of environment.”

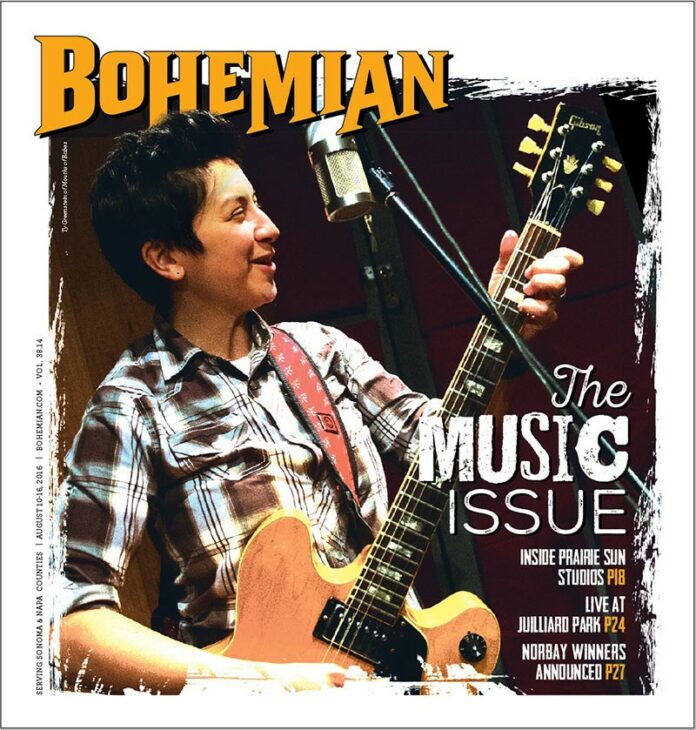

As we continue the tour, we move into Studio B, where Atlanta-based Americana duo Mouths of Babes is tracking vocals. Both members, Ty Greenstein and Ingrid Elizabeth, have called Sonoma County home for some years now; Elizabeth recorded with Wright at Prairie Sun in her old group, Coyote Grace.

“We were thinking of places all over the country where we wanted to record,” Elizabeth says. “I had such fond memories of this place. We wanted to work out here. It’s been great.”

As we watch the duo play a song, vocal harmonies swirling around the small room, Rennick’s smile widens. “That’s a moment. This is what I dig, when you feel the vibe, listen to bands like that,” Rennick says. “That’s why I wanted to be a studio owner. It’s not the finished record; it’s the life experiences, and it’s being around people being creative.”

“This place just has such a character and quality that really intrigues artists,” Nauseda says. “Any place where you create art is going to reflect that art, and this place is wonderful for that reason. It inherently imparts that quality on artists. Regardless of the acoustics, the gear, any of that—this place has a history, an iconoclastic history. And I really think that history, that vibe, all flows into the records.”

THE ENGINEERS

“There’s a really good quote, and I forget who said it,” Nauseda says, “but it goes, ‘A good engineer can’t make a bad band sound better, but they can make a great band sound greater.’ And I think that’s really true.”

Like everyone else working at Prairie Sun, Nauseda started as an intern, four years ago. A musician himself, Nauseda not only understands the craft, but also the passion that a good engineer must possess.

Now the studio manager, Nauseda splits time between running the front office and recording bands in session. “Everything we do is in service of the artist,” he says. “We’re all very dedicated people, dedicated to the music, the gear and the craft. There’s such an art that goes into this. I came up here because I care about helping people make music. It’s very fulfilling to help someone realize their dream.”

Wright also began his journey with Prairie Sun, in 2005, as an intern, learning under veteran Oz Fritz, whose credits include Tom Waits’ Mule Variations, Alice and Blood Money. Wright has been the studio’s chief engineer since 2009.

“Matt Wright is a badass,” Rennick says, “and you can quote me on that.”

THE GHOST

Apparently, some love Prairie Sun so much, they never leave. There are two farmhouses on the property where bands can stay while working, and Nauseda says he’s had multiple musicians tell him that a woman haunts one of them.

Residents claim that knocking can be heard each night at 11pm. “It could be the water heater,” says Nauseda. “But I prefer to think of the more poetic version.”

Stories like that remind Nauseda that the history of the land dates back further than a studio, further even than the chicken ranch. “So many different chapters to this place. It’s evolved, and it still evolves.”

Our last stop on the tour is Studio A, at the top of the hill. Studio A still has that new car smell, recently retrofitted with the help from designer Manny LaCarrubba. It also holds the studio’s largest mixing console, fitted with 80 inputs. The engineers can control any room from Studio A, aided by cabling that runs underground.

“Our digital system for mixing is as sophisticated as any in the Bay Area, and we’re really proud of that,” Rennick says. “We like to do it analog, that’s what we really like. The idea is to be everything to everybody, literally.

“In the end, nobody sees us,” he adds. “Nobody knows the record they’re listening to was recorded on a funky old chicken farm. They just listen and know, ‘That’s touching me.'”

Rennick relates a story he calls one of the studio’s great moments. John Darnielle, lead singer of indie rock band the Mountain Goats, was recording in the Waits room for the band’s 2005 album The Sunset Tree. “He said, ‘I need Mooka. I need Mooka [Rennick’s nickname],'” he says. “He’s singing a song about a wolf [“Up the Wolves”]. He pointed to the corner and said, ‘I want you to sit right over there.’ He made me sit in the room while he sang the lead vocal about five times, and he said, ‘I just want you to be here while I sing this.’ And that was a real honor for me. I knew that I was on the record in a certain sense.”

For Rennick and the crew at Prairie Sun, the camaraderie that comes from sharing in these experiences reminds them of the reason they chose a career in music to begin with.

“It’s a lot of work,” Nauseda says. “But the work is rewarding. We’re doing something not only to help people; we’re doing something that’s good for us, good for the property and good for the gear. There’s a whole lot of good.”

Musicians interested in recording at Prairie Sun can contact Nate Nauseda at 707.795.7011.