This is so bad, it’s good,” remarked Jerry Reilly when friend Scott Wilson presented him with Lucy in the Field with Flowers, the oil painting that first inspired the creation of the Museum of Bad Art (MOBA) in 1993. Wilson, an art and antiques dealer, had rescued Lucy from a pile of trash on the street, hoping to salvage and sell its frame before re-depositing the canvas in the garbage. But Reilly insisted on keeping the painting, and the duo soon found themselves collecting and soliciting donations of “bad art,” which they installed in Reilly’s basement along with the requisite track lighting. His subsequent house-warming-party-cum-art-show was a huge hit, attracting more than 200 guests, “and the next morning we decided to start a museum of bad art,” recalls his sister, Louise Reilly Sacco, a recently retired marketing consultant who now serves as MOBA’s “permanent interim acting executive director.”

While MOBA has long since outgrown Reilly’s basement and now occupies a pair of galleries, both within 1920s-era movie theaters (one in Dedham, Massachusetts, the other in nearby Somerville), it has stayed true to its mission of “celebrating artistic effort, however misguided.” Under the direction of current curator-in-chief and Boston resident Michael Frank, its collection now numbers more than 600 pieces (approximately 100 of which are displayed at any one time), almost all contributed by donors relieved to find someone—anyone—willing to take the works off their hands.

Yet like any fine art museum, MOBA is very particular about what it will appropriate for its permanent collection, accepting little more than 10 percent of what is offered. Factory art, tourist art, any work painted on velvet or that’s paint-by-numbers, any of the well-known kitschy motifs (dogs playing cards, et al.), anything by a child and anything remotely close to being pornographic is rejected out of hand.

Beyond that, the art “has to be original and sincere, and it has to be bad in a spectacular, interesting or noteworthy way,” Sacco explains. In other words, if you were walking past a gallery and saw the piece in the window, would you say, “Whoa, look at that”? She admits that there’s also a certain amount of subjectivity involved, as in, “Bad art is whatever our curator says it is,” before jesting that the museum’s “worldwide search” for a curator just happened to yield someone local, who just happens to own a tuxedo.

Owing to MOBA’s relatively strict standards, Frank encourages potential donors to email or send a slide or photo before mailing a work or leaving it outside one of the galleries, as the latter tends to irritate the Dedham and Somerville movie theater managers who provide MOBA with rent-free gallery space and don’t appreciate it when artwork of dubious quality suddenly appears on their respective doorsteps. As for the works that don’t fit the museum’s criteria, these are disposed of at biennial charity auctions, each piece delivered to the auction winner with a certificate that reads, “Rejected by the Museum of Bad Art.”

Categorical disqualifications aside, the most common reason a work is rejected is because it’s just plain boring. “It may be bad, but in a boring way. And many of the submissions just aren’t that bad. Artists who submit their own work—and it happens a lot—tend to be very hard on themselves. We have to say, ‘You’re just too good for us’,” claims Sacco. But in effect, self-submissions are a no-lose proposition for the artist. “If we accept their work, they’ve got a piece in a museum. And if we reject it, they can tell themselves, and others, that they were too good for MOBA,” she elaborates.

While People magazine once quipped that the artists of MOBA “aren’t in it for the Monet,” several professional artists have paintings on display, including Mari Newman, most famous for decorating her Minneapolis home and yard with an ever-changing display of sculpture that is sometimes characterized as “an eyesore.” And then there’s Roger Hanson, of Ocean Shores, Wash., who “paint[s] in the genres of impressionism, abstract expressionism and a tangent of abstract expressionism that [he] call[s] color expressionism,” according to curatorial copy. Hanson has a pair of paintings at MOBA, Coulda Been Marilyn Today and Half Polynesian, Half Norwegian.

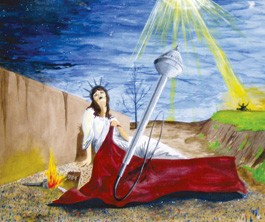

Even more surprising is that on at least one occasion, MOBA has launched an artist’s career. Consider the case of Bonnie Daly, whose brother-in-law donated Pablo Presley (pictured on a T-shirt), which led to an on-camera interview with CNN, which led to several commissions. “A few years later, she quit her day job and started supporting herself as an artist,” Sacco says.

Despite the occasional success story, MOBA faces many of the same problems as any other art museum. The main issue is generating enough revenue to keep the institution open, and since admission is free, the organization relies on merchandise sales (T-shirts and postcards) and also accepts financial contributions via its website. Paintings from the collection have also been featured in a pair of books, including last year’s Museum of Bad Art: Masterworks (Ten Speed Press), by Frank and Sacco.

And, believe it or not, from time to time MOBA has even had problems with theft. Most notably, in the museum’s earliest days, a man walked off with Eileen, and ultimately demanded a ransom of a $1,000, which far exceeded the $37 or so that the museum had offered in reward money. Nevertheless, MOBA did report the crime to the Boston police, which prompted a visit by officers from the city’s art theft division, who were trying to link Eileen to the infamous thefts from the Gardner Museum, as both crimes were listed in their records as “art theft of pieces of unknown value.”

“We explained that our ‘unknown value’ was on the other end of the spectrum. They were very nice and decided not to put a lot of effort into our case,” says Sacco, stating the obvious.

Anyway, the story had a happy ending, as MOBA got the painting back approximately a decade after it was stolen. As it turns out, the thief’s wife got fed up with having Eileen under the couple’s bed. “By this time, they had kids, and she was concerned about the example it was setting for the children, so she asked her husband to return it,” Sacco remembers. A transaction was arranged through an intermediary after MOBA agreed not to press charges.

Considering that the galleries are set in the unused portions of local movie theaters, MOBA security leaves something to be desired. As is the case with most museums, budgetary considerations preclude implementing many recommended security measures. In Dedham and Somerville, security is limited to a few fake security cameras (clearly marked as such), which, if nothing else, seem to deter children from engaging in shenanigans.

However, the presence of fake cameras didn’t deter an intruder from absconding with Rebecca Harris’ Self Portrait as a Drainpipe and leaving behind a note taped to the wall with the message “For $10 you can have your painting back.”

“The thief left no contact information, so there was nothing we could do,” says Sacco matter-of-factly. But as with Eileen, the case resolved itself in satisfactory fashion. “A few weeks later it was back on the wall with $10 taped to it,” she says. Yet in spite of the jokes, most artists are more than happy to have works on display at MOBA. “One you get past the name of the museum, you realize that we are giving artists an audience and celebrating their work,” Sacco explains.

“The main lesson for artists is that they should be adventurous, because even if they fail, they may still end up with something that people will respond to and gain recognition for their efforts.”

Visit the virtual museum at www.museumofbadart.org.