Ticket to Ride

High-speed rail is the answer to California’s clogged roads and airports, but will the politicians get it?

By Jeff Kearns

ON A HOT, smoggy Monday afternoon in August, Gov. Gray Davis quietly forecast the end of freeway building in California. Standing on a freshly built eight-lane roadway in Southern California’s Inland Empire, he was surrounded by orange Caltrans trucks, TV cameras, and a passel of state and local officials sweating in their suits. The noon ribbon-cutting ceremony in the middle of farmland attracted about 2,000 onlookers, who gathered beneath the new green highway signs pointing the way east to San Bernadino and Barstow.

The opening of the first phase of a 28-mile, $1.6 billion extension of Interstate 210 from La Verne to San Bernadino isn’t exactly big news, except to frustrated Inland Empire commuters and Vegas-bound Angelenos. But in his remarks, Davis said this freeway will be one of the state’s last for the foreseeable future, because California’s transportation spending policies have been changed by economic necessity. On a cost-per-mile basis, freeways don’t pencil out.

Instead, in the March primary, Davis will ask voters to back a proposition that would redirect state gas tax revenues to other kinds of transportation projects. If it passes, the state would raise $36 billion over 20 years. This is a sum of money that could, if the state gets its act together, build an environmentally clean and viable alternative to today’s gridlock–high-speed steel rail.

A modern version of a nearly 200-year-old technology, high-speed rail runs through almost all of the major cities in Europe and Japan. The United States has managed to ignore the idea for decades. The state of California may change that.

Proponents are working on a 10-year, $25 billion plan to link population centers in San Jose, San Francisco, Los Angeles, San Diego, and Sacramento with a 220-mph train, redirecting millions of travelers away from clogged freeways and airports. The trains could be up and running within a decade–if our elected officials ever get on board.

The barrier to high-speed rail in the United States isn’t, as some might assume, technology–it’s politics. State-of-the-art rail systems are there for the taking, but elected leaders generally won’t support anything on rails.

Choo on This

The California High-Speed Rail Authority is a tiny agency that can’t get the time of day from state lawmakers, who created the agancy in 1998 and never gave it the power inherent in its name. It remains in the embryonic stage, with four employees and nine appointed board members.

This year, Gov. Davis axed the authority’s entire $14 million budget request for environmental studies, leaving just the $1 million operating budget intact. Although the energy crisis zapped the budget surplus, what should be an important policy initiative wound up with crumbs: less than a hundredth of 1 percent of the state’s $80 billion budget.

Where It Will (and Won’t) Go: Although a final route hasn’t been selected yet, the high-speed rail line would serve all of the state’s major population centers.

Local Motion: Fasten your seatbelt. The merry-go-round that is North Bay public transit is coming back around.

Because it is still struggling to obtain even small amounts of state funding, the High-Speed Rail Authority employs just a handful of workers who, to cut costs, oversee a hired army of environmental and engineering consultants. So far, much of the early work has been contracted out to six teams, five of which are concentrating on a specific region. They have spent the last few years working on the extensive $25 million environmental impact report that the authority needs to complete before it secures funding.

And while Sacramento and Washington both lack the political will to support the high-speed rail effort, even one that could pay off in decades instead of months–politicians don’t like to look down the road past their next election–the choking off of its small budget risks major setbacks for the efforts already under way.

At the same time, the state continues to grow: The U.S. Census Bureau predicts that the state’s 34 million residents will number nearly 50 million by 2025–close to the current population of Italy.

And all of them won’t fit on freeways.

Speed Freaks

California’s high-speed train proponents, on the other hand, offer up a vision of quick, easy travel. In their alternate future, North Bay residents could board a train in San Francisco and find themselves at Los Angeles’ Union Station just two hours later–faster, in total trip time, than any airline flight. On express trains, there would be no advance ticket purchase needed, no check-in, no seat assignment, no baggage check, and no FAA restrictions. The highly automated, lightweight trains would run on dedicated tracks, fenced off, with no at-grade crossings. Because of safety and track maintenance, high-speed trains would not use the same tracks as existing passenger and freight trains. High-speed trains use continuously welded rails that are precisely aligned by laser equipment.

Planners forecast that the system could be carrying 42 million passengers a year by 2020, and even as many as 60 million a year. Segments of track could be carrying passengers–and producing revenue–by as early as 2011. Longer segments could be up and running in 10 years, with the entire 700-mile system open by 2016. Their vision is that in about 14 years, a bullet train will be solving California commuters’ woes and addressing a critical environmental and quality-of-life issue: helping Californians travel to work from the places they can afford to live.

Further down the tracks, if the system proves successful, profits could be used to extend service to other parts of the state.

Sounds great, right? So what’s the holdup?

The first holdup is: getting someone to notice.

“Unless we kill a busload of nuns, we don’t get network airtime,” rail advocate James RePass said in a speech last year. At the authority’s Aug. 1 meeting in San Jose, board members complained that the media were ignoring the issue. As Executive Director Mehdi Morshed updated board members on the authority’s near-empty bank account, one fed-up board member interrupted.

“Those of us who have been serving on this board are extremely frustrated,” fumed board member Jerry Epstein, a Los Angeles developer and Pete Wilson appointee. “It is absolutely a travesty that we have already spent so many millions of dollars, and for them to cut us off now is unbelievable.

“We should invest money in a proper PR firm that will force the legislators to come up with some money,” Epstein proposed. “We are absolutely living in the dark ages here. We must do something to wake up the people of California. Unless we have a rail system, we are going to be just mired in traffic.”

This, of course, is the understatement of the century so far.

Board members are scheduled to take some big steps forward at their November meeting in Bakersfield, when they will eliminate many of the routes under study and get significantly closer to choosing the final alignment that the system will use. “This is a critical milestone for the authority,” Deputy Director Dan Leavitt says.

But at the same time, the authority is staring down a funding crisis that could halt progress on the environmental studies unless state or federal lawmakers can come through with a new source of funding.

Not Amtrak

Perhaps in part fostered by the lack of media coverage on rail and mass-transit issues, the other hurdle for high-speed rail backers is the public perception that rail isn’t profitable because it isn’t popular–and vice versa.

Actually, extensive marketing studies commissioned by the authority show that not only is the potential ridership higher than first thought, but these riders are willing to put their wallets where their butts would go. According to Morshed, two thirds of the respondents polled said they would support the train and would be willing to support a quarter-cent or half-cent sales tax to finance its construction.

But the dismal reality of the issue is that government transportation dollars in the United States go to subsidize expensive highway and airport projects, not rail, and that lack of support from shortsighted elected officials is one of the main reasons that rail hasn’t caught on. In turn, U.S. rail service is generally slow, infrequent, expensive, and decades behind.

Ask most people about rail, and they’ll think of Amtrak, the company that gives trains a bad name. Amtrak’s new Acela (the name’s supposed to sound like acceleration and excellence–talk about unintended irony) connects Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Washington at speeds up to 135 mph. However, unimproved tracks limit Acela to slower speeds for many of those miles, and it continues to disappoint. Acela’s on-time record is poor, barely better than the shuttle flights it competes against, and ridership and revenue both sag below target levels. Nonstop service from Washington to New York was dropped, and a nonstop from New York to Boston never started.

Morshed wants to emphasize that what California has planned isn’t something like a clunky Amtrak upgrade.

“The main thing that is important to know is that when we talk of high-speed rail, we are not talking about anything that we have in this country,” he says. “This is a very fast train that’s comfortable and luxurious and safe and as fast as an airplane.”

Meanwhile, Amtrak flounders.

Nationwide, service is slow, often slower than driving. The trip from San Francisco to Los Angeles takes 12 hours, and costs more than airfare. Trains can cruise at 79 mph, but unimproved track (owned by freight train companies) often forces them to creep along at slower speeds. The rail network got a boost in ridership after the terrorist attacks, but will likely lose it again.

The heavily subsidized rail network is a private corporation that was formed when the federal government merged four dying passenger rail companies in 1971. Congress has demanded that it start operating in the black by 2003 or face big cuts or even defunding. Amtrak has pocketed $23 billion in federal funds since its creation. According to its 2000 Annual Report, even with ridership and revenues on the rise, Amtrak operated at a loss of $944 million.

But while Congress continues to push Amtrak to get its act together, lawmakers won’t give it the money it needs to succeed.

Amtrak Chairman and CEO George Warrington, quoted in the National Journal, grumbled that the United States, ranked by rail capital spending as a percentage of total transportation spending, is somewhere between “Estonia and Tunisia.”

Tokyo Go Go

Contrast Japan: The country unveiled its first 125-mph Shinkansen just before the opening games of the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo. Since then, the national rail system has been privatized, and the network continues to expand.

A few blocks from the Imperial Palace, Tokyo Station is the hub of the network. White and blue trains glide into the station on tracks elevated above the streets of the Ginza District every couple of minutes. They sidle up to the platform almost silently, with an electric hum and a whoosh of air. Delays are nearly nonexistent, and the average deviation from schedule can be measured in seconds, not minutes. Except for the large seats and abundant legroom, the interior resembles a plane. Cruising at 186 mph, the train sways only slightly.

The technology evolves through continual research and development. The Japanese have tested Shinkansen at 300 mph. In Europe, France opened its first TGV (Train à Grande Vitesse) line in 1981, and is also continuing to expand service. Germany’s ICE (Inter-City Express) trains kicked off service in 1991. Spain, Italy, and Sweden have also followed. A handful of other European countries, plus South Korea, Taiwan, China, and Australia, are in various stages of planning or building fast trains. Even cash-strapped Russia is building a high-speed line from Moscow to St. Petersburg.

But while high-speed rail has been unquestionably successful in Europe and Japan, where it connects almost every major city, those parts of the world have much higher population densities–Japan’s is about four times California’s–and also have governments willing to fund development and expansion. Japanese and European motorists also pay big bucks–$3 to $4 a gallon–for gas, which generates tax revenues used to fund mass transit.

Still, California’s growing pains have begun to push transportation planning into the public consciousness, and voters are becoming more receptive to using tax dollars to fund transit solutions. Sales tax increases passed last year in Santa Clara and Alameda counties would support this. Presumably, the greatest support for the system would come not from transportation planners and rail advocates but rather from L.A.-to-Bay Area travelers who have endured delays longer than the flight itself, or made the drive on I-5 without air conditioning in summer.

If We Build It . . .

From a small office on the top floor of a tall building across the street from the Capitol, Dan Leavitt points to the Sacramento train station, near the river. That’s where the northernmost terminus of the high-speed rail system will probably be built. According to projections, it will serve 7 million passengers a year, depositing them a short walk from the Capitol. (The station is in roughly the same location as the original terminus of the Transcontinental Railroad, which was completed in 1869. Ironically, though the Irish and Chinese immigrants who built that first cross-country rail link worked only with hand tools and dynamite, construction took just six years.)

In phrases honed from hundreds of presentations, Leavitt drops facts and explains background as if he’s reading off a printed paper placemat.

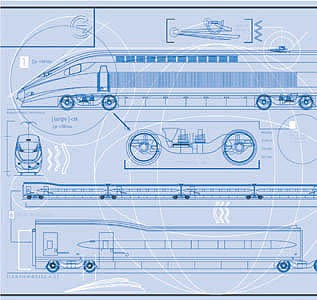

Planners are currently officially considering two technologies: Steel wheel on steel rail (the same as conventional trains and the bullet trains in Europe and Japan), and maglev, which uses electric currents to propel trains that levitate about an inch above a track.

Though both options are under study, maglev almost certainly won’t get the nod. Japan and Germany have built test tracks, and Japanese tests have hit 340 mph, but maglev still hasn’t carried paying passengers. On the other hand, high-speed rail technology has been available for decades and continues to improve.

Leavitt predicts the system could carry 32 million intercity passengers a year, plus 10 million commuters, while operating at a surplus–a boast almost no existing public transportation system in the United States can make. In addition to passengers, rail planners believe a statewide high-speed rail network could make additional money by carrying high-value and time-sensitive freight at night.

Morshed says the authority expects to operate at a surplus of more than $300 million a year, at a conservative estimate, and potentially as much as $1 billion a year. The hard part, however, is funding the $25 billion initial capital investment, especially after the electricity crisis deflated the state’s budget surplus. It may sound like a lot, but that’s only about a tenth of how much local, state, and federal cash will go to fund transportation projects in the state over the next 20 years. (To put the cost in perspective, Los Angeles city officials are planning a $12 billion expansion of LAX. SFO is proposing a $3 billion runway expansion.)

Former Santa Clara County Supervisor Rod Diridon Sr., a longtime rail evangelist, recently became a key figure in the drive to create the rail network, a move that may bode well for the project.

Diridon was appointed to the High-Speed Rail Authority board by Gov. Davis in June, and elected chair by board members in August. The son of a Southern Pacific engineer, Diridon himself worked as an SP brakeman in college. After a long career in politics, Diridon was named director of the Mineta Transportation Institute, a publicly funded transit think-tank at San Jose State. He was also a member of the state high-speed rail commissions that preceded the formal creation of the authority. (As perhaps further proof of the longevity of his obsession, Diridon is the only board member with a train station named after him.) Diridon’s appointment to the board could be an important shot in the arm for the program because of his political connections in Sacramento.

It doesn’t take much to get Diridon started on the subject of how the United States trails Europe and Japan in the mass transit department. “Europe spent $11 trillion upgrading an already superior transit system, and most of that was spent on high-speed rail,” he says. “We’re all bogged down in our commitment to outdated technology. They’re more advanced in using transit tools than we are. We’re developing transit systems that are bound by petroleum.”

But Diridon is confident that, although Americans lag, California’s system is far from doomed. “When it’s built, it will undoubtedly pay for itself,” he says, “and if we build it, I know that the public will embrace it.”

From the October 11-17, 2001 issue of the Northern California Bohemian.