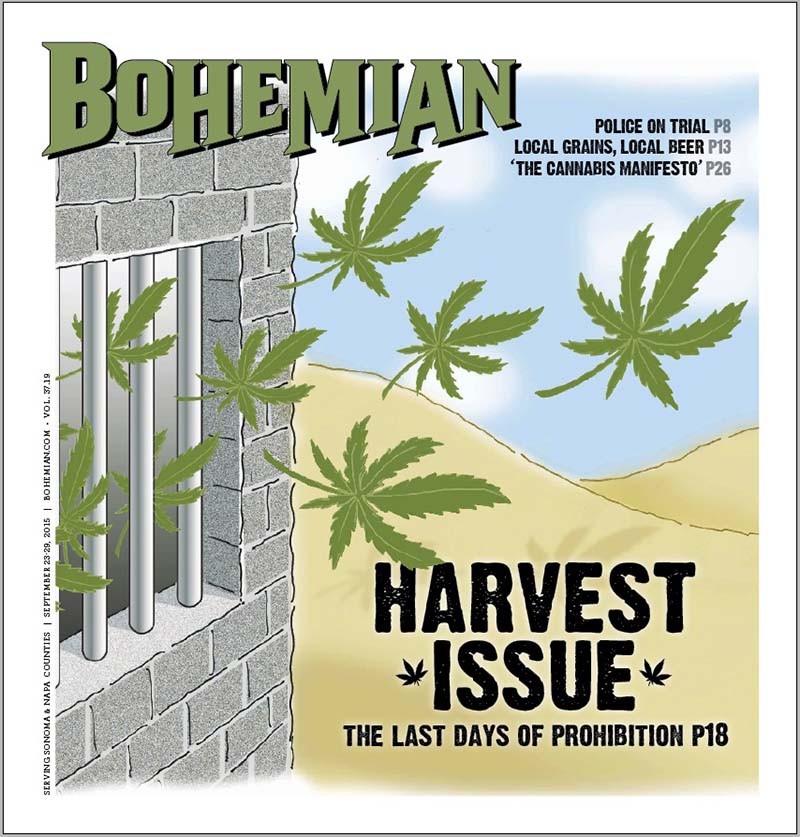

It’s harvest time in the North Bay, and that means two things: grapes and marijuana. For this year’s harvest issue, we thought we’d take a look at the latter crop, because this is a special year for Northern California’s cannabis industry. All signs are pointing to a ballot measure in the November 2016 election that will seek to legalize marijuana, although what that legislation will look like is far from clear. We have entered the last days of prohibition, and we’ll be covering the subject as the clock winds down.

There are a lot of moving parts associated with the cannabis economy and cannabis culture, so this week we decided to talk to some of the players.

We wanted to know: What are your hopes and fears as the state moves to join Colorado, Washington, Alaska and the District of Columbia?

Twenty sixteen is lining up as a turning point for cannabis reform across the country. Numerous states are poised to push legalization efforts. California, with its 40 million citizens and voracious appetite for freedom (and cannabis)—along with large pockets of resistance to such things—stands at the vanguard of the next round of legalization efforts. There are approximately 50,000 cannabis-related businesses in the state and 350,000 workers. California is poised to be the tipping-point for a whole new national policy on marijuana. If it works in California, it may work in New York. And Florida. Texas is another story.

“Peace in Medicine hopes adult use passes,” says Robert Jacobs, founder of the Sebastopol dispensary. “It is clear that public support has increased over time. The fact that this subject is being discussed in presidential debates demonstrates the huge advances made on this issue. We must end the needless prosecution of citizens for growing a plant.”

In what is emerging as a common theme among legalization supporters, he wants to see small-scale growers and operators protected under any new legislation.

It’s one thing for small-population states like Colorado to go legal, quite another for the nation-state of California. California has a roaringly diverse set of interests, some competing, and they all need to put together an initiative agreeable to all parties, even those who aren’t keen on legalization (i.e., statewide law enforcement organizations, which uniformly oppose legalization).

In the meantime, all signs are pointing in the direction of cannabis emerging as a campaign issue this year. If you watched the Republican debate on CNN last week, you now know that Gov. Jeb Bush smoked pot in high school, but his mom is mad at him for saying so. Carly Fiorina clucked that the marijuana of today is pretty potent stuff. And you know that New Jersey governor Chris Christie would shut down the Colorado experiment; he’s promised a renewed federal crackdown on the herb if elected president.

So we are anticipating a heavy convergence of national presidential politics and statewide efforts to free the weed, and we sure hope Hillary Clinton can take a deep breath and inhale the reality: cannabis freedom is emerging as a key civil rights issue over the next few years.

So read on, and let us know your hopes and concerns.—Stett Holbrook and Tom Gogola

Hezekiah Allen

Chairman and executive director, Emerald Growers Association

Hezekiah Allen’s hopes for legalization are clear: “What we’re working to do is end the injustice of prohibition.”

The hard part, he says, is coming up with legislation that makes matters better, not worse.

Any new law must address public safety by drawing a clear line between criminal enterprises and small-scale farmers and businesses, he says. It must regulate and protect environmental resources and clarify the law for small businesses. Getting those things in place is by no means guaranteed with no frontrunner initiative or legislation yet. The worst-case scenario would be two or more initiatives on the ballot, he says. With 50–60 percent support for legalization, competing initiatives could divide the electorate, leading to infighting within the cannabis industry and defeat at the polls.

“We need to win,” Allen says.

He wants any new law to protect the thousands of people who work in California’s cannabis industry. Leaving them out would be disastrous, he says.

“That’s a really bad situation to put small businesses in,” Allen says. “What sort of crisis would we have we created?”

As he sees it, the best way forward is to work within the medical marijuana regulatory framework legislators in Sacramento passed last week, and to make sure any new legislation is consistent with it.

“I think the policy work has been done,” he says.—Stett Holbrook

Omar Figueroa

Sebastopol’s Omar Figueroa pins his hopes for any statewide legalization effort on the thousands of mom-and-pop cultivators in the state whose livelihoods now stand in the balance. He hopes that in a legalized cannabis economy, they don’t get screwed by a vertically integrated economy, where might makes right.

“My concern is that these mom-and-pop operators will be pushed aside by big corporate interests,” Figueroa says. “We are already seeing this,” he adds, in the form of big-business dispensaries that can afford the lobbyists necessary to advocate before lawmakers. “Mom and pop are getting left behind. My big-ticket hope would be that we have an initiative that would allow these thousands of mom-and-pop cultivators to thrive under a legalized regime.”

Figueroa has other big dreams. He’d like to see the state lead the way in the creation of a cannabis genetics repository, “where all genetics are stored and accessed and made available for research,” and that it leads the way in the creation of social cannabis consumption, i.e., cannabis lounges.

He also wants any statewide cannabis regulatory package to include local boards comprising elected officials. These cannabis commissioners would reflect transparency in the emergent new weed economy, he says, “but the fear is that instead of having elected officials choosing what laws get enacted, we’d have political appointees engaging in regulatory arbitrage—the making of regulations for the benefit of the few.” —Tom Gogola

[page]

Chief David Bejarano

California Police Chiefs Association

Chief David Bejarano heads the police force in Chula Vista, Calif., and he’s also top dog at the California Police Chiefs Association, a statewide organization whose hopes and concerns over the 2016 legalization of cannabis boil down to: We hope it doesn’t; we’re concerned that it will; and we hope to have a place at the table if it does.

In an interview, Bejarano identifies numerous areas of concern when it comes to cannabis legalization and its intersection with law enforcement; those concerns mirror many of those brought to bear by his organization as they’ve worked closely with lawmakers to come up with chiefs-friendly language in a statewide medical-cannabis policy hashed out by the Legislature this year.

If legalization must happen, says Bejarano, his organization is keyed on public-health concerns, especially among youth whose brains are at risk at an early age; an increase in drug-related DUIs on state roads; and heightened illicit sales if the state sets the cannabis tax so high that it encourages a black market. Which brings up that violent and entrenched Mexican drug cartel that Colorado doesn’t have to deal with, notes Bejarano.

Despite whatever tax boon might come to the state, Bejarano argues that it won’t “offset the social cost of cannabis,” which he says will be paid in the criminal justice and healthcare systems.

“We’re standing side by side with the [California] State Sheriffs’ Association, and oppose legalization,” he says. “But if it’s voted upon by the voters, we have to be at the table to protect public safety, and push for strong regulation. And we should be at the table.”

Bejarano says he hopes that if the state does go legal in 2016, it won’t take 20 years for lawmakers to come up with a statewide regulatory apparatus, as happened with medical cannabis.

He hopes cannabis revenues that can be realized are redirected into healthcare, rehabilitation programs and in nipping back the “higher burden on the enforcement side, especially the drug DUIs. We need more drug-recognition experts. That is the challenge for us. We don’t have enough of these officers.”

Closer to home, I asked Sonoma County district attorney Jill Ravitch for her hopes and concerns over cannabis. A spokesman says she’s not ready to go there yet. “She’s going to choose not to comment on it. As we get closer to legalization, reach out again.”—Tom Gogola

Anonymous Cannabis Grower

Pot growers are not a monolithic group. Some grow outdoors. Some grow inside. Some own their land and others rent. Some have quasi-legal status as suppliers to medical marijuana dispensaries, and others grow for the black market. So how legalization might affect them depends on what kind of grower they are. I spoke with one indoor grower (who requested anonymity) about what his hopes and fears are if legalization comes to pass. His biggest concern: price.

The price for a pound of weed (now about $3,000 to $3,600 for indoor-grown) continues to fall because of growing supply, but also changing techniques out-of-doors. Many outdoor growers now use a technique called light deprivation that involves tarps and hoop houses to compress growing cycles by getting plants to flower sooner and more often. That means that what once was a glut of outdoor-grown cannabis in October and November now gets spread out, eating into the premiums that indoor-grown herb commands outside of the “flood” of the traditional fall outdoor crop harvest.

His other concern is whether new legislation will protect small-scale growers or open the door to deep-pocketed mega-growers who force out little guys like him.

With those factors in play, this grower echoes what many in the industry say: “No one really knows what’s going to happen.”

On the upside, legalization may create greater demand and new opportunities for him. “Colorado ran out of weed when they legalized it. It’s a weird supply-and-demand act people are doing in their heads.”—Stett Holbrook

[page]

Dylan Marzullo

Co-owner, Deep Roots

As the co-owner of a hydroponic growing and gardening supply shop in Santa Rosa and Sebastopol that caters to cannabis growers, Marzullo gets asked about the run-up to legalization all the time.

“That’s the question of the decade,” he says. “I have this conversation at least five times a day.”

He hopes business will stay the same, but if voters approve legalization, he realizes his industry will grow, and with it will come more competition from big retailers like Home Depot and Lowe’s. Those stores already carry some of the soil amendments and fertilizers that Deep Roots carries.

“We’re at the mercy of where the market goes.”

He says he’s carved out a narrow niche, and his edge is know-how and a willingness to deal.

“Big stores are not willing to negotiate on a larger level. They’re asking full retail price for everything.”

He hopes growers will appreciate the role they play in what is, for now, a small, local community.

—Stett Holbrook

Kevin Sabet

Smart Approaches to Marijuana (SAM)

For Kevin A. Sabet, director of the Drug Policy Institute at the University of Florida, co-founder of Project SAM (Smart Approaches to Marijuana) and advisor to three U.S. presidential administrations, the move to legalize weed is all about one thing: money.

“There’s a huge industry that wants to make money off of other people’s problems,” Sabet says by phone, on his way to speak to schools and communities in Hawaii about the risks and effects of “21st-century marijuana”—much stronger than the marijuana of 10 to 20 years ago. “And I’m very concerned about that.”

Sabet founded SAM in 2013 because he was concerned with the false dichotomy of the marijuana debate: that we either have to legalize marijuana or incarcerate people for it. “I thought there were many better, smarter solutions on these two extremes,” he says.

Sabet’s biggest worry, he says, is with the adolescent brain. “My concern is that access and availability and legalization would increase the influence of an industry that’s going to downplay the harms.”

Last week, Sabet spoke to schools in Marin, where he says that many parents were unaware of the negative effects of marijuana, and thanked him for bringing the issues to their attention. “I heard a lot of people saying that this is not an issue that folks want to talk about around here—that this is kind of something that gets slipped under the rug,” Sabet says. “And that it’s really an elephant in the room because, you know, no one starts their heroin addiction putting a needle in their arm, right?”

Learning from Colorado about how the marijuana industry has taken hold should be frightening for Californians, Sabet says, who have taken a strong stance against tobacco.

“I find it particularly ironic when certain people talk about how anti-tobacco they are and anti–tobacco industry, yet they’re OK with sort of rolling out the red carpet for the marijuana industry.”—Molly Oleson

Random North Bay Pothead

Marin County, Somewhere

As if in a dream, I encountered a random North Bay pothead over the weekend. He was wandering around an undisclosed location in West Marin, smoking a joint while eating a plum and reading the latest Bolinas Hearsay News. I approached this man, a wild-eyed hippie in dirty, patched coveralls, as he blew a big puff of smoke in the general direction of capitalism, which random North Bay pothead disdains as a matter of principle.

I approached random North Bay pothead and asked, What are your hopes and concerns when it comes to cannabis legalization in California? To which he responded: “Are you a narc?”

I convinced him I was a reporter on a search for hopes and concerns as they relate to cannabis legalization.

“I’m concerned that you’re walking up to people you don’t even know and asking them dumb questions,” he said. “But I’m hopeful you might join me for a puff of this fine, stanky homegrown, so that we might get to know one another before I answer your questions in a more thoughtful manner.”

Wisps of smoke blew across Elephant Mountain, which we had by then mounted—though the memory is hazy, at best. The man finally admitted from atop the massif, “I’m concerned that when cannabis is legalized, my entire self-generated identity as a West Marin outlaw vagrant will go up in smoke, and I’ll have nothing. I’ll be nothing, nobody. Yet I’m hopeful that I’ll be able to go grab a gram at the Tamalpais Junction 7-11 to go with my Slurpee. That would be cool.” —Tom Gogola