Every weekend since December, the Sonoma Ecology Center has been leading hikes into local wildlands to see how they are faring after the Tubbs and Nuns fires whipped through Sonoma Valley.

The free hikes are popular, with 20 to 30 participants showing up every time for the two- to three-mile venture around Suttonfield Lake at the Sonoma Developmental Center, or 3,200 feet up Bald Mountain at Sugarloaf Ridge State Park and other properties.

“The bad news about the fires is very evident and reinforced through the media and personal experience,” says Caitlin Cornwall, a biologist and research program director at the Sonoma Ecology Center (SEC). “We’re doing the walks to give people a more nuanced experience of what fire means. You have to experience the rebound of the land before you can believe this is a true aspect of the fires.”

We are sitting outside the SEC offices on a prematurely warm day, accompanied by a woodpecker tapping overhead and the call of various birds.

“It’s difficult for people to hold in their heads and hearts that fires are frightening, and also beneficial and necessary. We’re looking to a future where it’s normal to see regular active management of wildlands. The idea that land should be left untouched shows a lack of understanding of what the land needs. The land needs us and we need the land. That is the message that has come from the Native American people.”

At Sugarloaf, the fire burned

80 percent of the 3,300-acre property. Since the fires, park staff have removed more than 60 downed trees and repaired burned-out steps, installed new retaining walls and creek bridges. Now the risk of landslides, higher here than anywhere in the county, is the top concern, says park manager John Roney. But there has been very little rain since November.

As we clamber up a trail toward Bald Mountain, the highest point in the park, it does appear, despite the chill wind, that the land is breathing more freely. We’re headed for the chaparral ecosystem near the top of the mountain, the domain of a large variety of shrubs and plants subject to frequent wildfire. For two months after the Tubbs fire, the land was completely black. Most of the chamise was seared to its bare trunk. The few trees, mostly manzanita and madrone, were black and bare too.

“It was a moonscape,” says Cornwall, who visited the area as soon as it was safe to do so. It wasn’t until early February that Sugarloaf could welcome visitors.

The first rain brought a smooth, green carpet of fresh grass, appearing all the more brilliant in the absence of the dead grasses destroyed by fire.

About halfway up the mountain, we find ourselves in a beautiful open meadow surrounded by hills. “You can see the fire line here,” Cornwall says. On one side, a field of mixed grasses; adjacent to it, a brilliant green field where the fire had been.

I return the next day and catch a ride to the top with a park steward. As we drive through the cattle gate on the narrow fire road, the vista that spreads before me is unlike anything I have seen before.

Nearly five months since the firestorm, it’s an eerie sight. Areas once dense with bushes and undergrowth are nothing but blackened hardpan with the charred remains of the plants. The fire was so hot in some places trees vaporized, leaving a skeleton of white ashes on the ground. The stale smell of burnt vegetation still lingers in the air.

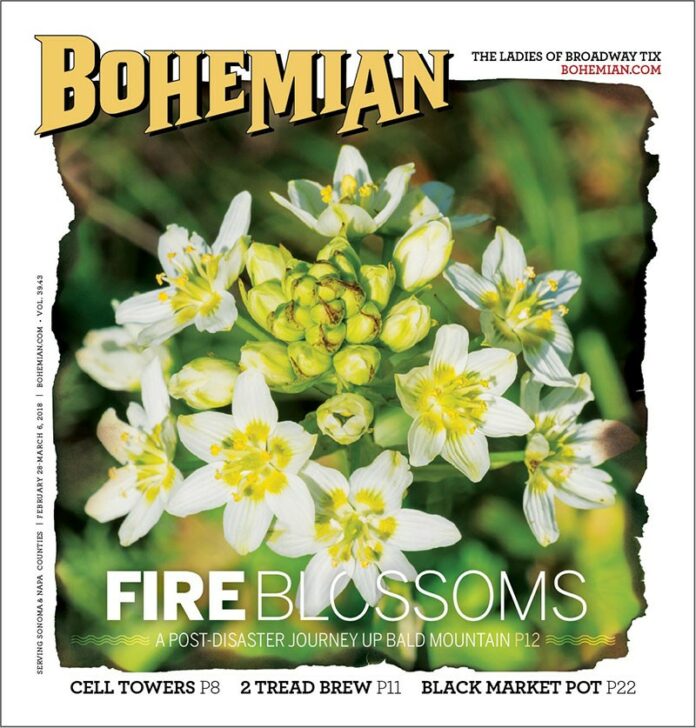

However, signs of life are visible. Little clusters of plants have emerged. The delicate white flowers of Fremont’s star lily, a bulb rarely seen here, are abundant. Little shoots of other plants are visible, among them the wavy leaf soap root, whispering bells and purple needle grass. These bulbs and seeds have evolved to bloom in the higher temperatures.

Other plants find unusual ways to germinate. Madrones that looked completely burned are resprouting from the canopy, proof that trees that appear dead probably aren’t.

[page]

Coast live oaks are sending out new leaves from along their branches, not the usual way to sprout, Cornwall says. “Leaves normally sprout from the tips,” she says. “The tips release a hormone that inhibits growth in other parts of the tree, but since the tips burned, they no longer produce the hormone. The phenomenon is similar to what you see when you prune your fruit trees—leaves start to appear on the branches.”

Another shrub, the toyon, is sprouting new leaves from the burl at its base instead of from the burnt branch tips.

The most common chaparral plant is the chamise, whose seeds have adapted to sprout only after the higher temperatures of fire. Feathery seedlings of chamise are already in view.

Some plants sprout from their roots. The fire’s heat penetrates only an inch of the soil, and the root system beneath may be intact beneath a blackened trunk that appears dead, but often the root system, which is wider than the canopy, has survived. Hence most trees should not be removed unless they are dangerous. Some oaks will take three to six years to reveal that they are alive.

Even dead trees are useful, providing habitat for creatures like the endangered spotted owl, a native of these forests, while fallen tree trunks, left to rot, produce insects, bacteria and fungi that other animals eat.

Chaparral has adapted to fire, which naturally occurs every 30 years or so. But if fires occur more often, as is happening due to human activity, the seeds will lose the ability to sprout, according to the California Chaparral Institute. Wild grasses, which are much more flammable, will start to take over.

Because of the danger of accumulated undergrowth and cramped trees, Cornwall supports prescribed burns.

“The plant community produces more biomass and more biodiversity when there are fewer stunted, crowded plants,” she says. “Ash fertilizes soil. Fire stimulates the growth of bulbs and reduces the cover of nonnative grasses.” There are exceptions, though. “If their needles burn, Douglas firs won’t come back. Neither will bay trees.”

In a landscape where fires are a natural feature, prescribed burns would make us safer. Insurance companies, however, don’t agree. Cornwall says that’s understandable, though she hopes the industry will flip from “not insuring properties that do burns to not insuring properties where burns are not done.”

A recent study by the Little Hoover Commission, an independent state oversight agency, supports Cornwall’s view. Its report, “Fire on the Mountain: Rethinking Forest Management in the Sierra Nevada,” concludes that “California’s forests suffer from neglect and mismanagement, resulting in overcrowding that leaves them susceptible to disease, insects and wildfire.”

One hundred twenty-nine million trees have died in California forests during drought and bark beetle infestations since 2010, which represents a significant fire hazard. Instead of focusing almost solely on fire suppression, the report states, the state must institute wide-scale controlled burns and other strategic measures as a tool to reinvigorate forests, inhibit firestorms and help protect air and water quality.

“Dead trees due to drought and a century of forest mismanagement have devastated scenic landscapes throughout the Sierra range,” says Little Hoover Commission chair Pedro Nava. “Rural counties and homeowners alike are staggering under the financial impacts of removing them. We have catastrophe-scale fire danger throughout our unhealthy forests and a growing financial burden for all taxpayers and government like California has never seen.”

Plants grow back; houses don’t. A visit to Bald Mountain is a powerful experience, but it is also a reminder: like so much else going on in our world today, the threats appear to be moving toward us faster than our willingness to confront them.

Fire hikes will continue through June, when the wildflower display will be at its peak. Check the calendar at sonomaecologycenter.org for the schedule.

Stephanie Hiller is a freelance writer and Santa Rosa Junior College adjunct instructor. She lives in Sonoma.