One of the biggest flushes of morel mushrooms in living memory, a sought-after, spring-time ingredient at many top-tier restaurants, is now bursting from the ground in the Sierra Nevada, just west of Yosemite National Park. Due to a land closure that has turned political, however, nobody can get to them.

Roughly 400 square miles of woodland burned last summer in California’s Rim Fire. The blaze was one of the largest in state history, consuming 257,000 acres of trees, mostly in the Stanislaus National Forest. It destroyed scores of buildings and caused an estimated $54 million in damage.

Forestry officials say that dead trees with the potential to fall on roadways, trails and campgrounds pose too great a threat to allow public access. That leaves millions of pounds of morels—and millions of dollars to be made off the prized ‘shrooms—stuck in the ground.

San Rafael’s David Campbell, a 40-year mushroom-hunting veteran, says the government has no reason—or right—to close the area. “I think they’re being extremely unfair and self-serving in the way they’re handling things,” he says.

The area is closed to everyone—except loggers, that is. “They say it’s to protect natural resources, and they’re logging the bejesus out of it,” says Campbell.

The penalty for entering the off-limits part of the forest is up to $5,000 and six months behind bars. So far, says Don Ferguson, spokesperson with the Forest Service, most violators have only received warnings.

Curt Haney, president of the Mycological Society of San Francisco, has a similar stance.

“It’s dangerous any time you go in the woods,” he says. “There are bears and mountain lions. So why not ban hiking all the time?”

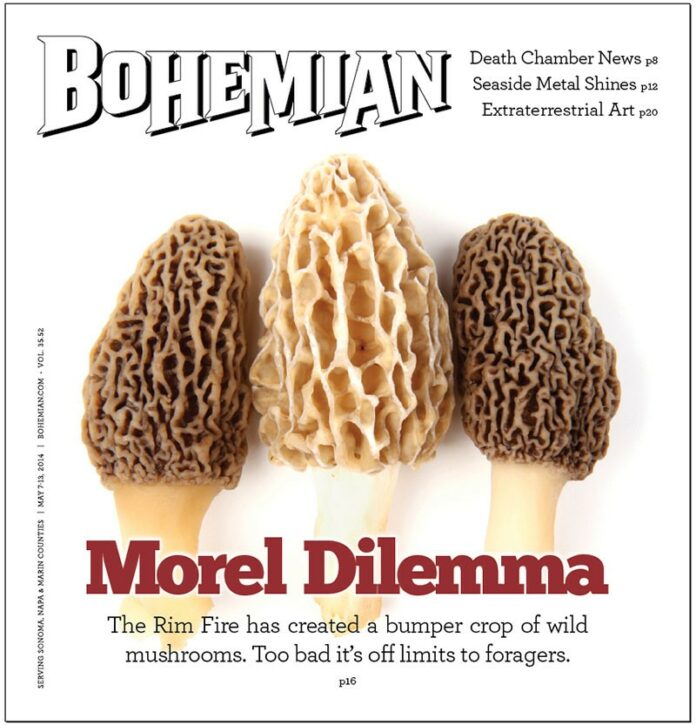

There are hundreds of different kinds of edible mushrooms, but morels are special for their flavor, size and fleeting availability. These aren’t the type of mushrooms found on pizza or at the self-serve salad bar; they aren’t even found in most grocery stores. These are special-order, shipped-around-the-world mushrooms.

Duskie Estes, chef and owner of Sebastopol’s Zazu, loves morels. “They have a deep, earthy flavor,” she says, that goes great with spring flavors. “Peas and morels are killer.”

Morels are often only procured through foraging trips with a seasoned guide, and denizens of the North Bay are lucky enough to have them within driving distance, when conditions are right. Morels can grow almost anywhere, even out of concrete-layered sidewalks. But for reasons not entirely clear to scientists, they grow most prolifically from burned ground, where ash and wood char have leached into the soil. Morel hunters covet recently charred forests for this reason. Haney has been lobbying for access to the closed area for months with his club members and fellow mushroom aficionados.

[page]

His group has written to U.S. Forest Service officials and lawmakers—including U.S. Sens. Barbara Boxer and Dianne Feinstein, Rep. Tom McClintock, R-Roseville, and the Tuolumne County Board of Supervisors—but none has shown interest in exempting mushroom hunters from the closed area. With trees ready to fall and heavy branches dangling by splinters, government officials say it’s simply too dangerous.

“I’ve heard from a lot of morel hunters who are just dying to get into the forest up there,” says Ferguson. “They’re saying it’s one of the best places to hunt in years, and they might be right, but it’s just not safe now.”

Campbell disagrees, to say the least. “I think the Forest Service is doing a huge disservice to the public,” he says. “They’re throwing out excuses that don’t really hold water.”

An expert who leads educational mushroom hikes and a past president of the San Francisco Mycological Association, Campbell says he knows of some folks who have taken the risk and hunted in the closed Rim Fire area, despite warnings. “The roads are just littered with these signs,” he says. “It’s basically a state of civil disobedience up there.”

The Forest Service is currently assessing the Stanislaus National Forest, locating all “hazard trees” near heavy-use roadways and planning their removal, a process that should begin this month, Ferguson says. The agency is also launching a bigger-scale project, termed the Rim Fire Recovery Project, that aims to remove salvageable timber from 30,000 acres of the charred forest.

But mushroom hunters, who have been antsy to explore the region for months, argue that wind and rain during the winter have probably knocked down most potentially dangerous loose branches, making the forest fairly safe for entry. They also say the federal agency should have done cleanup work sooner, before morel season.

“They’ve had six months since the fire to clear out the hazard trees, and they haven’t done anything,” says Robert Belt, a mushroom hunter from the foothills town of Sonora.

Even after hazardous trees along high-use roads are removed this month, the region will remain closed to the public as a longer-term project begins to clear and restore the forest. The Rim Fire Recovery Project, Ferguson says, will assess some 30,000 acres of national forest land from which trees will be removed by commercial loggers. The project will aim to remove trees lining low-use dirt roads, he adds, as well as salvageable timber deeper in the forest.

Funds from the logging will be used to restore the forest, which Ferguson says must be cleared before it can be replanted. Proceeds from the tree removal will support reforestation of the area.

The Rim Fire Emergency Salvage Act (HR 3188) would mandate the USDA sale of “dead, damaged or downed timber resulting from the wildfire” without the usual environmental survey requirements and without judicial review. It was introduced to the floor last September but has yet to be voted on in the House.

[page]

Meanwhile, on April 28 Susan Skalski, forest supervisor for the Stanislaus National Forest, approved hazard-tree removal along 194 miles of high-use roads and 1,329 acres of national forest land. Environmental groups and the logging industry had voiced support for such a proposal the week prior.

“If we can get a buck back for the wood, that can really help us get through this,” Ferguson says.

Todd Spanier, a peninsula-based commercial mushroom supplier, says his company, King of Mushrooms, is coming up short on supplies for customers—especially morels.

“I have people calling me from throughout Europe wanting dried morels, and I’m trying to decide how to deliver,” Spanier says.

The state’s entire economy, he adds, is taking a hit. Spanier has estimated that the closed portion of the Rim Fire zone contains $23 million worth of morels. That, he says, is based on a recent $30 per pound wholesale value.

Spanier warns that businesses in small communities near the scorched area will suffer if throngs of mushroom hunters, including the nomadic groups of commercial foragers that roam the Northwest, are not allowed to use the area.

“You have cafes and restaurants and lodging where all these mushroom hunters would be going if they were allowed in,” Spanier says. “A lot of these places have been really hurt already by the fire closure.”

But not all is lost for morel hunters. Already, several Stanislaus campgrounds, dusty with soot and ash, have been reopened.

“Morel hunters are welcome to hunt mushrooms around these sites,” Ferguson says. “It’s a big area, though, and you can go anywhere you want in the forest, but we are enforcing the laws and we have officers out there watching that people stay in the open areas. We’re going to do our best to protect people from the hazards out there.”

Rebecca Garcia, spokesperson for the Stanislaus, says that other areas that burned last summer are currently open to the public.

“There are a lot of burns that we’ve already opened, and there will be plenty of morels growing there,” Garcia assures.

But the rest of the affected area won’t be open to the public until Nov. 18, according to a temporary Forest Service order, long after the morel season is over.

Morels grow most prolifically in a burn zone in the spring immediately following a forest fire, but second-year morel blooms, Haney says, can produce even more mushrooms.

“The area will be productive next year too,” he says. “We’ll still get some morels.”

Calls to Skalski were referred to Pam Baltimore, Forest Service media spokesperson for the Rim Fire, who didn’t return calls before deadline.

‘Bohemian’ staff writer Nicolas Grizzle contributed to this story.