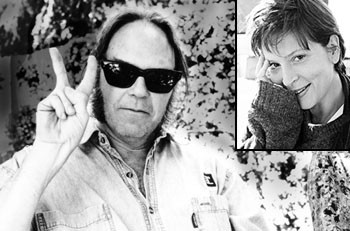

Once We Had Heroes: Neil Young was once king of the protest song; now he’s all for “going after Satan.” Folksinger Leslie Nuchow (inset) tries to focus on music’s healing power.

Is Protest Music Dead?

Music used to be the dominant voice against war. Now it’s easier to shut up and get paid.

By Jeff Chang

Ever since John Lennon and Yoko Ono led a raucous crowd of flower-toting, peasant-bloused hippies in the pot-hazy chorus of “Give Peace a Chance,” it seemed to have been a pop axiom: When the United States goes to war, the musicians call for peace.

Opposing war hasn’t always been a popular position, but it has created some great music. During the Vietnam era, songs like Edwin Starr’s “War,” Jimi Hendrix’s cover of “All Along the Watchtower,” Funkadelic’s “Maggot Brain” and “Wars of Armageddon,” Jimmy Cliff’s “Vietnam,” Country Joe and the Fish’s “I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die Rag,” Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Bad Moon Rising” and “Have You Ever Seen the Rain?” and Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On” turned defiance into a raging, soaring, brave, and melancholic gesture of community.

Even our allegedly apathetic post-Lennonist generation has extended the tradition. When Bush Senior sent troops to Kuwait in 1991, rappers Ice Cube and Paris trained their verbal guns on the White House in “I Wanna Kill Sam” and “Bush Killa,” while Bad Religion and Noam Chomsky split a 7″ into a no-war-for-oil seminar. Antiwar music has become a time-honored balance to the “bomb ’em all and let God sort ’em out” fervor. So why, since Sept. 11, have we heard so little new music protesting Bush Junior’s war on evil?

Artists who were once outspoken peaceniks seem to have lost their certainty or even switched their position. For years, U2 led crowds in chants of “No more war!” during their concerts. But during their surrealistic Super Bowl half-time performance this past January, they offered deep ambivalence: a stark display of the names of Sept. 11 victims set to “Beautiful Day.”

Neil Young’s “Ohio” memorialized Kent State University’s murdered antiwar protesters of 1970; his “Cortez the Killer” condemned imperialism. Now we find him on his post-Sept. 11 cut “Let’s Roll,” singing, “Let’s roll for freedom / Let’s roll for love / Going after Satan / On the wings of a dove.”

Young wrote the song to honor the heroes of Flight 93 who subdued their hijackers and paid the ultimate price. But if you believe “Let’s Roll”–with its Bush-reduced ideas of evil and Satan–is a cry for peace, you’ve probably already cleaned out your bomb shelter and reviewed your duck-and-cover manual.

As Leslie Nuchow, a Brooklyn-based folksinger who has been touring the country, says, “Speaking on or singing anything that’s critical of this country at this time is more difficult than it was a year ago.”

We’ve seen dozens of acts quietly bury their edgier songs. We’ve seen radio playlists rewritten so as not to “offend listeners.” And we’ve seen Republican officials and the entertainment industry–long divided over traditional-values issues such as violent content and parental advisory stickering–bury the hatchet. White House Senior Adviser Karl Rove has been meeting regularly with entertainment industry officials to discuss how they can help the war on terrorism.

The result? Not unlike the network news, there’s been what a media wonk might call a narrowing of content choice. Think eagle- and flag-adorned anthologies of patriotic music, prefab benefit shows screaming “Consumer Event!”, Alan Jackson’s “Where Were You (When the World Stopped Turning),” and Paul McCartney’s “Freedom.” Perhaps this may all be good for the record business–no small thing for an industry that found itself shrinking by 3 percent (about $300 million in revenues) last year. But it’s hardly the stuff of great art.

Gonna Win, Yeah

Where are the alternative voices? Let’s start with hip-hop, the most socially important music of our time and, until recently, the most successful. Hip-hop’s sales plunged last year–by 20 percent, according to Def Jam founder and rap industry leader Russell Simmons.

And so did its vision. While Congress debated the Patriot Act and air strikes left Afghan cities in ruins and untold innocents dead, Jay-Z and Nas declared their own dirty little war for the pockets (if not exactly the minds) of the younger generation.

Jay-Z’s dis of Nas, “The Takeover,” was based on a sample from the Doors’ “Five to One,” an anti-Vietnam War song released during 1968’s long, hot summer whose title supposedly alluded to a demographic menace: five times as many people under the age of 21 as over.

Here’s Jim Morrison’s original: “The old get old / And the young get stronger / May take a week / And it may take longer / They got the guns / But we got the numbers / Gonna win, yeah / We’re taking over!” Here’s Jay-Z’s slice: “Gonna win, yeah!” Released on Sept. 11, his Roc-a-Fella Records album The Blueprint sold 465,000 copies.

Nas came back with Stillmatic, an album seemingly conceived from a marketing blueprint. Over a decade ago, Nas debuted during the height of hip-hop’s social consciousness. To appease these aging fans, he included songs on Stillmatic like the decidedly non-flag-waving “My Country” and “Rule,” which bravely ask Bush Junior and the secret bunker crew to “call a truce, world peace, stop acting like savages.” But kids love that shit-talking, so there’s also “Ether,” dissing “Gay-Z and Cock-a-Fella Records.” Guess which of these songs gets the most rewinds?

In fact, many musicians are commenting on the war; they just aren’t being heard. On a new album for Fine Arts Militia called We Are Gathered Here . . . , Public Enemy’s Chuck D has set scathing spoken-word lectures to rockish beats by Brian Hardgroove. Chuck takes apart the war-mobilization effort and condemns the arrogance of the president’s foreign policy on “A Twisted Sense of God.” But while the song will be available as an MP3 on his website (www.slamjamz.com), the album has found no distributor yet.

He says, “You got five corporations that control retail. You got four who are the record labels. Then you got three radio outlets who own all the stations. You got two television networks that will actually let us get some of this across. And you got one video outlet. I call it five-four-three-two-one. Boom!”

When the World Ends

Message music is being pinched off by an increasingly monopolized media industry suddenly eager to please the White House. At least two of the nation’s largest radio networks–Clear Channel and Citadel Communications–removed songs from the air in the wake of the attacks. Songs like Drowning Pool’s “Bodies” and John Lennon’s “Imagine” were confined to MP3 sites and mix tapes. And while pressure to maintain blacklists has eased recently, the détente between Capitol Hill, New York, and Hollywood–unseen since World War II–has tangible consequences.

Bay Area artist Michael Franti and Spearhead were invited last November to play the Late Late Show with Craig Kilborn. Franti obliged with a new song, “Bomb Da World.” Yet the song’s chorus–“You can bomb the world to pieces / But you can’t bomb it into peace”–was apparently too much for the show’s producers. Months later, and only after a Billboard magazine article exposed the story, the clip finally aired.

“It’s funny,” Franti says. “In the past, I’d hear some folksingers singing folk songs or ‘Give Peace a Chance’ and think, God, this is really corny. But then you realize, in a time of war, it’s a really radical message.”

Little wonder that artists have quietly censored themselves. The Strokes pulled a song called “New York Cops” from their album, and Dave Matthews decided not to release “When the World Ends” as a single. It’s easier to do an industry-sponsored benefit or to simply shut up and go along than to fight for a message and find it pigeonholed.

As monopolies segment music into narrower and narrower genre markets to be exploited, protest music becomes the square peg. Perhaps the question isn’t only whether protest music can survive the war but whether protest music can also survive niche marketing.

Take KRS-One’s new album, Spiritual Minded. In part a reaction to the Sept. 11 attacks, the album reconciles Christian spirituality with a radical notion of diversity–putting together Bronx beats, Cantopop, biblical chapter and verse, and the word “peace” and the Islamic greeting “As-salaam Alaikum” in the same song.

“We live in a Christian nation,” he says. “I can only give the public that which it can digest. So I put this album out. The door swings open. Christians are like, ‘Yeah, wow, KRS! He finally came over.’ Now I’m over. Now let’s talk.”

But if this is his most subtle effort yet to promote a message of peace and unity, it is still a record that needs to be marketed. So while Spiritual Minded has been a dud in the hip-hop world, it topped the less lucrative Gospel charts earlier this year.

Even indie labels no longer provide an alternative, says Joel Schalit, Bay Area-based contributor to Punk Planet magazine and member of dub-funk band Elders of Zion. Schalit’s new book, Jerusalem Calling, features a chapter indicting the indie-punk scene, a movement that began as a highly charged reaction to Reaganism and major labels and ended up a calcifying, apolitical, “petite bourgeois” feeder-system for the same majors.

“I think our generation has started to move in the direction of formulating its own distinct progressive political positions, but in many respects, I think that the trauma that was Sept. 11 has thus far stopped them from doing anything new,” he says. “There haven’t been people rushing out to print 7″ singles attacking American foreign policy like there was during the Gulf War.”

He adds, “A lot of label owners, especially on the independent level, are very concerned that promoting ideology is not the same as promoting art.”

If that sounds reasonable at first glance, consider the question that Bay Area antiprison activist and Freedom Fighter Music co-producer Ying-sun Ho asks in reference to rap: “You don’t think a song that talks about nothing but how much your jewelry shines has a political content to it?”

Acts like Jay-Z are seen as artists with universal appeal, whereas niche marketing lumps together acts that have little in common. The subcategory of “conscious rappers,” for instance, has been used to sell Levi’s jeans and Gap clothing to college-educated, disposable-income-spending hip-hop fans. In this logic, it’s not the rappers’ message that brings the audience together, it’s what their audience wears that brings the rappers together.

Part of the recent wave of conscious rap acts promoted by major labels, rap duo Dead Prez disdains the entire category. Positivity isn’t politics, rapper M-1 argues. Hip-hop has not yet produced much antiwar music because a lot of conscious rappers were never clear about their political positions in the first place, he believes, and Sept. 11 revealed their basic lack of depth.

“There’s a lifestyle that goes with not being aligned with the politics of U.S. imperialism. It’s not just a one-day protest,” he says while working in Brooklyn on Walk Like a Warrior, the follow-up to 2000’s Let’s Get Free. “We’re in a new period. A lot of people are not seeing what has to be and are looking at it from just a red, white, and blue angle.”

Hard Rain Gonna Fall

But perhaps, in this connected world, we also possess accelerated expectations. History shows that radical ideas don’t take hold overnight. World War II’s hit parade featured sentimental escapism like Bing Crosby’s “White Christmas” and sugary patriotism like the Andrews Sisters’ “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy.”

During the ’50s, a progressive folk movement emerged, but it wasn’t until Bob Dylan, Phil Ochs, and Joan Baez revived folk amid the early ’60s ferment of student organizing that ideas of disarmament and racial justice began to take root.

As Craig Werner, professor of African-American studies at the University of Wisconsin, Madison and author of A Change Is Gonna Come: Music, Race, and the Soul of America, tells me, “The foundation of the anti-Vietnam War music was in the folk revival. It was almost as if there were an antiwar movement that was in place that was doing the groundwork. They’d been writing those kinds of songs for years when Vietnam came around.”

Werner dates the emergence of anti-Vietnam War music to ex-folkie Barry McGuire’s 1966 hit, “Eve of Destruction,” a song that faced widespread censorship. “I was growing up in Colorado Springs, which is a military town. The week that ‘Eve of Destruction’ came out, it broke onto the Top 20 charts on the local station at No. 1. And then was never heard again.”

That moment is not near in these early days of the war on evil. In the long run, Nas’ “My Country” and “Rule,” with their laser focus on cause and effect, or Outkast’s antirecessionary global humanism on “The Whole World” may prove to be more prophetic.

For now, confusion and flux and omnidirectional rage carry the day. Bay Area rapper Paris recently addressed the second Bush in “What Would You Do,” a track on his upcoming Sonic Jihad album: “Now ask yourself who’s the one with the most to gain / Before 9-11 motherfuckas couldn’t stand his name / Now even niggas waiving flags like they lost they mind / Everybody got opinions but don’t know the time.”

Ghostface Killah seems to have captured the moment on Wu-Tang Clan’s “Rules.” Addressing Osama bin Laden directly about the attacks on New York, he raps, “No disrespect, that’s where I rest my head / I understand you gotta rest yours too.” But since bin Laden has brought the bombs–“Nigga, my people’s dead!”–it’s officially on: “Mr. Bush, sit down! We’re in charge of the war.”

Healing Force

Still, musicians must do what they do, and the story is not yet over. Folkie Leslie Nuchow believes in music’s ability to transform the people who listen to it, and she doesn’t waste a lot of time worrying about who will distribute it. Recently, she recorded the mesmerizing “An Eye for an Eye (Will Leave the Whole World Blind).” Accompanied only by piano, she elaborates on Gandhi’s famous line mostly in a tortured whisper. It’s only available through her website (www.slammusic.com).

Nuchow–who likes to point out that our national anthem “glorifies war” but has agreed to sing for U.N. troops stationed in Kosovo later this year–believes music is not merely a product, it’s a process. After watching the Twin Towers collapse from her Brooklyn building, she spent that evening agonizing over what to do next. “I kept on saying to myself, what could my political action be?” Then she realized, “I’m a musician. Ri-i-i-ight. Let me do music!”

She went to demonstrations and gatherings, and handed out fliers inviting people to come and sing the next morning. About 50 people showed up. They walked through the streets singing “This Little Light of Mine,” “America the Beautiful,” and “Dona Nobis Pacem (Give Us Peace).”

“We walked as close to Ground Zero as we could get, and we sang for the firefighters,” she says. “We sang for the rescue workers and the firefighters. We went up to the hospitals, and we sang for the doctors, and we sang for the volunteers. And then–this was the hardest–we went to sing for the families who were trying to find out what happened to their loved ones.”

Nuchow recalls that the music did exactly what it was supposed to do. “People wept. Other people came and joined us,” she says. “And to me, that’s action. That’s making a statement through music, using music as a healing force.”

And for now, perhaps, that’s more than enough.

From the May 9-15, 2002 issue of the North Bay Bohemian.