Seeing Red

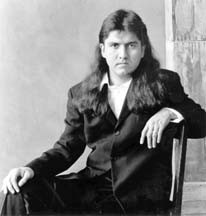

MARION ETTLINGER

Portrait of the artist: Poet, author, and standup comic Sherman Alexie doesn’t smile for the camera.

Author Sherman Alexie is one angry young man

THERE’S A KILLER on the loose, a lone man with a honed blade and a particular predilection for removing the blue eyes and the hairlines from white heads. Terrorizing Seattle, he silently walks the night streets, embodying that which Caucasians hate the most: the red man. Or is it the red woman? Whatever–whites and reds just don’t mix, each group caroming off each other in a racial fury that lies so close to the surface that we are each and every one of us just a Buck knife away from committing heinous acts of homicidal brutality.

Buy it?

Well, people are buying it by the droves, buoying up sales of Sherman Alexie’s novel Indian Killer (Atlantic Monthly, $22), a whodunit with no who and plenty of anger to go around.

“You know, it’s not like I’m walking around like [Nation of Islam leader] Louis Farrakhan or something,” says Alexie, speaking by phone from his Seattle office. “I don’t live my life with all of this anger, and when I was writing this book, it was cathartic in some ways. Actually it was a very easy book to write, and actually–I enjoyed the process,” he chuckles, “as much as you can enjoy writing a book about interracial murder.”

A Spokane/Coeur d’Alene Indian who grew up on a Pacific Northwest reservation, Alexie knows firsthand of what he speaks. The author of two other books of prose–The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven (Atlantic Monthly, 1993), and Reservation Blues (Atlantic Monthly, 1994)–as well as several books of poetry, at a creaky age of 29, Alexie is coming darn near to his stated goal of publishing some 10 books before he gets really old and turns 30.

A direct result of Alexie’s feeling of being misunderstood, Indian Killer was written in reaction to criticism. “In my first two books of fiction,” he says, “people talked about how dark and depressing they were, how full of Indian angst they were–and they weren’t. They were very funny and comic novels. There was certainly a lot of tragedy, but a lot of comedy as well. So I sort of wrote this book as a response, to kind of give people an idea of the kind of anger and the kind of rage that is in the Indian community, as well as that which is in the white community, directed toward Indians.”

And show it he does, producing matter-of-fact prose delineating white men beating, cussing, raping, verbally abusing, and beating again the modern-day Indian (Alexie’s preferred term). As for the Indian characters in the novel, well, they just laugh–homeless or no, in anger or at peace. Laughter is Alexie’s sinew of characterization for the native peoples.

“Indians are funny,” he says simply. “I mean, the funniest groups of people on the planet that I’ve ever been around are Indians and Jews. So I think that that says something about using humor to ward off centuries of oppression and genocide. I’ve heard Jews make jokes about Hitler. I’ve heard Indians make jokes about Custer–that takes a lot of strength.”

Centering around the slow mental dissolution of John Smith, an Indian of indeterminate lineage adopted into a white family (and presumably going crazy as a result of being raised by whites and denied his true heritage), Indian Killer weaves the many stories of Smith, the Native American activist Marie–so distraught by her color as a child that she sandpapers her face–her psychopathic cousin Reggie, and assorted evil white types who variously appear as Indian wannabes, stupid do-gooders, and racist pigs. This is not pretty reading, nor is it recommended for perusal around the lunch table.

Alexie is unconcerned.

“I figured reaction to the book would be mixed,” he says. “People are freaked out by it. I mean this book to start discussion, I mean this book to be controversial, I mean this book to affect and offend.”

Included in the scenes of Indian Killer is one that deeply affected Alexie in reality. A bright child, he transferred from the reservation schools at a young age, assimilating into the predominantly white institutions of the Seattle area. Seated one afternoon in a pizza parlor with his girlfriend and other friends, young Alexie watched a painfully drunk Native American man stumble into the restaurant, look blankly around, and fall thickly onto a stool. Alexie’s girlfriend leaned forward. “I hate Indians,” she hissed. No one said a word, suddenly acutely aware of Alexie’s skin color.

This scene appears in the pages of Indian Killer, savagely illuminating how it feels to be thus humiliated. “It’s about completely ingrained racism, so ingrained as a fundamental problem that people aren’t even aware of it,” he says. “That’s the problem, that people aren’t even aware of it, and that this young woman whom I loved when I was 14, could be capable of such an incredibly cruel statement.”

Indian Killer wasn’t cathartic enough to wring clean the lifetime of oppression lived by Alexie. “I’m a colonized man,” he stresses, “we’re a colonized people. This is South Africa here, and people don’t want to admit that.

“The United States is a colony, and I’m always going to write like one who is colonized, and that’s with a lot of anger.”

Sherman Alexie reads from and signs Indian Killer on Thursday, Oct. 10, at 7 p.m. Copperfield’s Books, 138 N. Main St., Sebastopol. Free. 823-8991.

From the October 3-9, 1996 issue of the Sonoma Independent

This page was designed and created by the Boulevards team.

© 1996 Metrosa, Inc.