Rotten Apple

Summer of Sam.

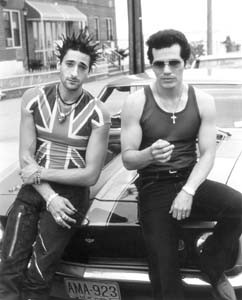

David Lee

‘Summer of Sam’ plunges into the dark underbelly of ’70s New York City

By Nicole McEwan

IT WAS THE BEST of times; it was the worst of times. New York City, 1977. Inflation was at an all-time high while the disco craze held the nearly bankrupt city in thrall. People danced in the streets even as crime skyrocketed. The sexual revolution was in full swing, AIDS was just a rumor, and cocaine was not known to be addictive. Downtown, punk rock was exploding at CBGB’s. Uptown, Studio 54 was becoming an enduring symbol for the decadence of the era. At Yankee Stadium, Reggie Jackson led the home team to a dramatic World Series victory.

Then temperatures hit the triple digits, causing blackouts and mass looting. It was Christmas in July, but New York was in mourning. A killer was on the loose. His name: “Son of Sam.” He operated without motive or meaning. His taste ran to young brunettes; his weapon of choice: a .44. By the time of his capture, six young people were dead and seven more injured.

It was an age of hysteria and scapegoating–and the paranoia that gripped the Big Apple was telecast across America, exposing the metropolis’ rotten core. In 1977, only one man “loved” New York. His name was David Berkowitz, and he was a madman.

Summer of Sam, starring Mira Sorvino, John Leguizamo, and Adrian Brody, is director Spike Lee’s wildly ambitious, boldly provocative attempt to capture that collective insanity on film. In a film that is part Scorsese homage, part cinematic jazz, Lee has fashioned an intriguingly experimental epic as disjointed as its title character’s thought processes.

Using a canvas as broad as the boroughs themselves, Lee focuses not on the hunter, but on the prey. In the process the director, one of America’s few genuine auteurs, finds the extraordinary in the ordinary, asking not the easy questions, but the ones with no concrete answers. Paranoid schizophrenia made Berkowitz kill–but what festering social ills turned hundreds of New Yorkers into rabid vigilantes?

Summer‘s script, written by actors Michael Imperioli and Victor Colicchio (and adapted by Lee), is based on their memories of that infamous period–a time in which no one, not even the parish priest, was absolved from suspicion.

Using distorted camera lenses, skewed angles, and lurid red filters, Lee introduces Berkowitz obliquely, using the killer’s filthy trash-strewn apartment as a metaphor for the lunatic’s cluttered mind. Berkowitz’s physical appearances are brief, even in the murder scenes–which are brutal, but realistically matter-of-fact. His presence is constant, however. Excerpts from his deranged letters are read throughout the film, and his activities are tracked and updated through blaring headlines, cops’ conversations, and a TV reporter (Lee in a comic cameo).

To his credit, Lee doesn’t profess to understand the murderer. This detached storytelling style simply identifies Berkowitz as a catalyst. Fittingly, his shadow looms large over the other characters, for they are the true subjects of Lee’s blisteringly honest character study. They include Vinny (Leguizamo), an oversexed hairdresser juggling a marriage, several mistresses, a nasty coke habit, a classic Madonna/whore complex, and Dionna (Sorvino), the faithful wife stranded on a massive pedestal carved from Vinny’s Catholic guilt. Though they clearly love each other, the only place the couple really connects is on the dance floor. When discos begin closing early because of the murders, their problems escalate.

VINNY’S BEST FRIEND Richie (Brody) is back in Queens after living in Manhattan. The punk singer’s combat boots and stiff and spiky hairdo enrage his old gang, who immediately label him a freak. Only Vinnie and Ruby (Jennifer Exposito), the neighborhood tramp embrace his new persona, though they know nothing of his secret life as a bisexual hustler.

Meanwhile, New York’s finest are so desperate for a break in the case that they approach a group of wise guys led by Luigi (Ben Gazzara) for help. As terror grows with each shooting, Luigi organizes the local toughs, whose ham-handed attempts to solve the crime result in mindless brutality.

Then the lights go out, followed by the blind and rampant thievery that left flourishing neighborhoods decimated for years to come. Soon thereafter, Lee’s apocalyptic soap opera implodes. The result is a breathtaking climax whose montage of dazzling images, married with the driving, insistent chords of the Who’s “Don’t Get Fooled Again,” should leave an audience in a state of emotional enervation.

Lee, who’s known for his meticulous casting, hits the jackpot here. He will likely be credited for “discovering” Adrian Brody, though the actor has been on the fringes of stardom for years. Brody’s sinuous frame, his hound-dog countenance, and sheer natural ability shine.

Leguizamo is easily his match, essaying the perfect pitch of pathetic sleaziness. Dionna is the role that should earn Sorvino another Oscar. But the film’s big discovery is Esposito, who gives Ruby (a girl whose sexuality is a weapon that’s been used against her) a quiet desperation.

Summer of Sam, like most of Lee’s work, has been the subject of media scrutiny. This time, the “controversial” director is being accused of making money off Berkowitz’ victims. It’s typical that the pundits are missing the point. This film is less about “The Son of Sam” and more about the masks that people wear and the darkness that lies just beneath the surface–a universal topic well worth exploring.

Entertainment reporters might better serve the arts if they asked the question that nags me every time I see a Spike Lee film: How can an artist whose work is so consistently challenging gain so little support or acknowledgment?

From the July 1-7, 1999 issue of the Sonoma County Independent.

© Metro Publishing Inc.